WINNER OF BEST WEBSITE AWARD

Go to "About" page for details!

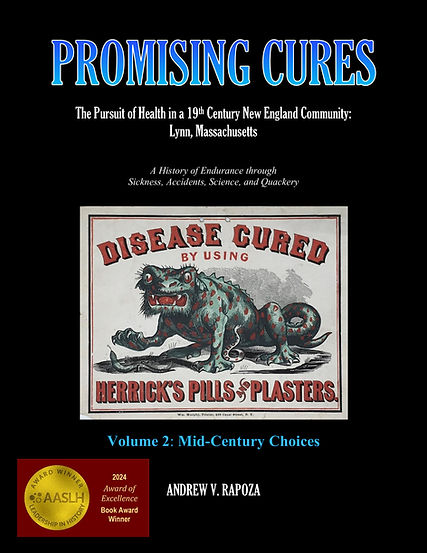

PROMISING CURES

The Pursuit of Health Remedies in a 19th-Century New England Community: Lynn, Massachusetts

.png)

All 4 volumes are FREE online at FamilySearch.org

(Just click on the desired volume above, then click on the "VIEW INSIDE" box below the cover and create a [free] account to view the pages.)

Also for sale on

.png)

2024 Book Award Winner - American Association for State and Local History

PROUD MEMBER

of these two great organizations

that support

COLLECTORS OF HISTORY

The Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors

The Ephemera Society of America

Discovered,

Uncovered, & Recovered.

Welcome to

secrets of life

in the past.

19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies

Have you sometimes wondered what it would have been like to live a hundred years ago? Or 200 years? Or 400? Would you like to see it through the eyes of the people who lived it—their hopes and fears, their trials and triumphs?

Let's examine ephemera, the artifacts they held and used. We'll also read the private letters and diaries they wrote, alongside newspapers and other documents that marked milestones in their lives. These pieces of ephemera give us a glimpse into their daily experiences.

There are plenty of books that teach about people of the past by peering down at them through a microscope—but I prefer walking next to them and letting them tell me about their lives themselves.

Join me—let's find out together.

Harmful Healers

in the 17th Century Massachusetts Bay Colony

The sick and injured struggled to survive – but so did their doctors:

a Witch (so they said), a Pirate (sort of), and a Loose Cannon (definitely).

by Andrew V. Rapoza © 2023

Pure fantasy: happy Pilgrims, all dressed in black and white, inviting happy Indians to a yummy Thanksgiving turkey dinner. It was a pretty picture to color with crayons when you were a little kid, but let me tell you what it was reallly like. There was little to be happy about in the 1600s. Few managed to keep healthy, and how can you be happy when you're not healthy? Scientific understanding of just about anything to do with health and medicine was little better than it had been in the Dark Ages. Death was a sudden and frequent invader of most homes in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Outside of Boston and Salem, the colony was spread throughout the challenging wilderness. Most colonists were isolated and had to resort to whatever or whoever was available for medical help: perhaps a local midwife or minister, a tavern keeper or apothecary, or the occasional visit of a wandering physician. But sometimes the healer was a victim as well – they often risked their own lives, even as they tried to save the lives of their patients. Being a healer in the town of Lynn was risky business during the 17th century. Planted between Salem and Boston, it saw its share of shady and menacing characters who promised cures and even performed surgery. Colorful and sometimes hair-raising stories of healing in the first century of European settlement could be told from every village and outpost of the colony, but for now, Lynn will step forward and represent the rest. Lynn was like most other settlements in the colony: a few remote clusters of buildings near sources of water, some tillable land, and woods full of timber, fruits, and game, and individual homes spread in all directions, even more isolated than the villages. They relied on their own wits and the nature around them for their shelter, food, and medicine. They could afford little time and even less money to go to Salem or Boston to buy items; it at least saved time when itinerants traveled to their little town, offering some goods for sale or services for hire. Beyond a few homemade medicines and poultices made in most homes, Lynn folk often relied on others to provide health services. Sometimes such healers were literally outsiders traveling through but other times they got treated as outsiders because of the peculiarities of their healing efforts or their behavior. The stories of two such men and a woman who tried to heal in Lynn will take you back to a place and time better read about than lived in. The three very different healers had one thing very much in common: they struggled to avoid death by something far more dangerous than a horrible, loathsome disease – vindictive people. THE LOOSE CANNON That would be Phillip Reade. This physician lives on in the long trail of court records that are smeared with his name. It’s hard to say how good he was as a doctor, but there were a bunch of people who didn’t like him one bit. His home was in Concord on the western edge of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but he traveled all over the colony to ply his skills. Court records reveal that in the last five months of 1669, he had traveled through Concord, Billerica, Lynn, Charlestown, and Cambridge. The Concord constables were well exercised in attempting to serve Reade with many warrants, but they seldom found him at home. On one occasion they rode twelve miles to Sudbury to catch up to the traveling doctor.[1] Another court record found Reade at Goodman Clarke’s tavern just one day for his patients in Reading, then a month in Lynn taking care of a Mr. Hawkes’ leg, and finally on to Salem “to visit my patients there.”[2] In his travels, Reade carried a rapier and often enjoyed the company of another traveler. Most of the paths he traveled were remote and secluded; the companionship of friends and sword probably gave him peace of mind amid the potential problems with wolves, wildcats, bears, rattlesnakes, Indians, highway robbers, and other such road hazards of 17th-century Massachusetts. Reade visited patients’ homes by the wayside, but concentrated his activities at inns and ordinaries because they were places where people gathered. It wasn’t just coincidence that innkeepers and ordinary licensees from Sudbury, Concord, Charlestown, and Reading were involved in court actions for and against Reade. As public houses and local landmarks, these facilities were ideal breeding grounds for patients and conflicts. Reade had a contentious personality that didn’t endear him to many; he was frequently in court being sued or suing someone else. In 1669 he was sued for slandering a midwife in Concord.[3] In another case that year, Reade filed a complaint against Martha Hill for raising false reports that “he had Cured Sara Wyman of a swelling under her chin and another under her Apron.”[4] Deponents all heard Martha claim that “the New docktor” had said Sarah was pregnant, but no one heard her suggest Reade had performed an abortion, as he had claimed in his complaint. In puritanical Massachusetts Bay Colony, the accusation of performing an abortion would have not only destroyed the physician’s reputation, but would likely have sent him to the gallows. Reade’s opinions and actions irked none more frequently than the church. In 1669 he was fined £20 for railing against a Concord minister, saying in part that the reverend was selected by a bunch of “blockheads who followed the plowtail.”[5] He was also chastised for saying that the illness of a female patient came from attending the minister’s long-winded sermon.[6] In 1671 he proved that he was also not a devotee of spiritual healings and was imprisoned for his blasphemy: “Philip Read of Concord Chirurgeon or practitioner of Phisick for not having the fear of God before his eyes & being Instigated by the divill ... on a motion ... to pray to God for his wife then sick blasphemously Cursed bidding the Divill take yow & yor prayers.”[7] Reade’s ways may have won him some allies, but they created enemies as well; indeed, more than one acquaintance threatened to “take the blood” or “knock out the brains” of “docktor Reade.” In August 1669 warrants were issued for Concord’s constables to apprehend Robert Williams because “doctor Mr. Philip Read ... doth live in fear of his life.” Among several witnesses, Reade’s new father-in-law testified that he heard Williams vow to “have the blood of Dr. Read.” Other deponents recalled Williams swearing he would “get a club and ... knock out the doctors brans” and the next morning that he had actually gotten a club and vowed to be Reade’s death. The depositions leave only a small clue why Williams hated Reade so much, “Dr. Read had given him such language as that he would not bear it though it cost him his blood.” Williams ran away before a verdict was rendered.[8] In a different case, Reade claimed that another of his melancholy enemies “had borne him a spleene ever since he came to Concord.”[9] In yet another action, Reade brought a defamation suit against Ambrose Makefasset for saying Reade’s mother “was or is a whore.”[10] What made Reade so difficult to like seemed to have more to do with his social weaknesses than his medical skills. He had a quarrelsome character that found more passionate expression than was usually prudent. In subsequent trips to Lynn, Reade made no effort to curtail his cantankerous disposition. He and John Gifford, the former agent of the ironworks in Lynn, were bitter enemies. Reade accused Gifford of cheating a relative out of £1000. When chance brought the doctor and Gifford together, epithets of “cheating dog” and “cheating rogue” were vehemently exchanged.[11] Reade added salt to the wound by incriminating that Gifford’s wife, Margaret, was a witch, “for there were some things which could not be accounted for by natural causes,” and that others had been “strangely” and “badly handled by her.”[12] Near the end of September 1679, John and Margaret Gifford were in Reading at Goodman Clarke’s tavern at the same time as the traveling healer. Reade was in Reading at his usual time of month to see his patients from that area. When John Gifford recognized the voice in the room adjacent to him and his wife to be that of Reade, he went straightway to the doctor and began quarrelling. Reade told Gifford to leave the room because he was attending to some patients, but Gifford refused. The two exchanged threats and demeaning names and stopped short of a fight only because there wasn’t enough space in that room for Reade to wield his rapier. Gifford left the room, but returned again with his wife who had some choice words of her own for the doctor, saying that “she was cleare of that he accused her of and that she should appear one day to be a Child of God when he should not.” The Giffords returned to Lynn where John told some of the townspeople “he had met with the Cowardly Dog Doctor Reade ... [who] drew his rapier at him ... he would make [Reade] Eate the point of his own rapier.”[13] A month passed, but the animosities did not. On October 31st, the antagonists met again, this time on the road to Salem; Reade was traveling towards Salem with a friend and Gifford was riding home from Salem alone. The events that followed depend on the storyteller. Gifford complained to the court of an incensed, murderous doctor who vowed to have his blood and that when passing each other on the road, the doctor took him by the shoulder and tried to push him off his horse, swearing, “he would have the blood of Such as I was.” Gifford managed to stay on his horse, but when past the doctor by about three horse lengths, he saw the doctor had drawn his sword and was riding back to attack him. “he presently made a thrust at me ... which I defended with takeing his Swoard blade in my hand though to the Cutting of me. Upon which he then Lett drive at my head. haveing nothing in my hand to defend myselfe but a small burchin twig he cut me o[n] the Elbow to the bone ...” The doctor was about to attack Gifford again, but someone was approaching on a cart, so he road off, swearing he would meet up with Gifford again and would have his blood.[14] Reade painted quite a different picture for the court with him as the innocent who was wronged and abused and Gifford as the man possessed. He claimed that when they met on the road, Gifford hit him in the chest and the face, pushing his lit pipe so far down his throat that it made him spit up blood and he also kicked him so severely that it broke his shinbone. The doctor said that Gifford swore “you hors Doctorly Dog” then picked up stones and threatened to “knock my braines out” along with other threats that made him fear for his life.[15] Neither man was ultimately exonerated. Reade had pressed against the Giffords in another direction during the assault trials by launching a formal complaint against Margaret Gifford for witchcraft. He even accused John Gifford of “haveing Sum familiaritye with Satan or his instruments.”[16] The court did not heed the inference about John, but based on Reade’s promise of more evidence on Margaret Gifford, she was ordered to appear at the next court three months later. John Gifford tried in turn to sue Reade in Superior Court for slanderously reporting that Margaret Gifford “had bewitched his wife and childe and that Shee should walke with him the sd Read hand in hand flesh, blood & bone in her own person two miles together.”[17] Ultimately, however, Margaret Gifford never had to go to court to answer for Reade’s accusations. The strain of constant financial hardship, coupled with the pressures of trials and the rigors of an itinerant medical practice, manifested themselves in what may have been Reade’s greatest temptation: alcohol. Virtually everywhere Reade traveled, people reported occasions of seeing him in an incoherent, drunken stupor. He was seen riding toward Concord in the winter of 1670, swaying to and fro upon his horse, speaking some things madly and swearing by the name of God two or three times.[18] He was drunk in Charlestown in the late summer of 1669, such that he could not speak rationally.[19] John Buss was in Reade’s company at Salem in August 1669, and saw that Reade was incoherent and couldn’t ride well. Buss further testified that he saw Reade so drunk at Concord that “he could not goe without stagering or speake rationaly and several other times both at Concord at Woburne & other places, where I accompanied him hee has Drunke to much.”[20] Others remembered Reade in Charlestown, swearing, “by ye name of god and wishd his soule damd to hell if he went not home yt night and [he] went not” because he was drunk.[21] Ann Adams of Cambridge recounted for the court how Reade came into her house one evening near the end of 1669, “much overtaken in drinke, & in such a condition that wee could not get rid of him, but were forsed to entertaine him till the morneing and that he uttered sundry evile & reproachful termes against Captain Gookin” (one of the magistrates who frequently presided in Reade’s trials), like “Captayne Hobby Horse,” “Captayne Glaze Eyes,” and “Captain Clowne.”[22] While Phillip Reade got mixed reviews from patients, his character was the critical weakness that prevented him from achieving lasting notoriety. He was contentious, opinionated, and fiercely inde-pendent, and the flames of all three were fueled by rum. A tongue that was often let loose against church and enemies and too often loose for drink sometimes put him outside the law and in conflict with the colony. Yet after each sentence was served and each fine was paid, Read returned to the same towns, taverns, and patients that were his practice. Phillip Reade’s career forced him to wrestle with demons of witchcraft and alcohol during his travels over the many miles. THE WITCH A widow named Ann Burt was one of those witches, or so Phillip Reade and others claimed. Science, superstition, and conjecture were never far apart in 17th-century medicine. The holes of ignorance were filled by suspicion and fear when no empirical explanation for physical, mental, or emotional abnormalities was clearly evident. Unexplainable illness or one that didn’t respond to treatment were often considered the work of witches. As demonstrated by the Salem witchcraft trials of 1692, there was no question in the minds of Puritans, from the humblest to the loftiest, that witches were real and many tried to protect themselves from the witches. In 1698 Cotton Mather scolded the colonists for their use of common objects to magically protect against evil: “Scores of poor People … did secretly those things that were not right against the Lord their God; they would often cure Hurts with Spells, and practice detestable Conjurations with Sieves, and Keys, and Pease, and Nails, and Horse-shoes, and other implements.”[23] Despite Reverend Mather’s chastisement and call to repentance for using charms, evidence remaining in original Lynn shows that many families were discreetly practicing counter-magic to fight off witches and their familiars. Most of Lynn’s seventeenth-century buildings have disappeared; only nine houses are known to have survived (to 2022) since their construction from 1629-1725, but seven out of nine still contain marks or objects that were designed to keep the witches away. The wary occupants of these Lynn homes had hexafoils, slash and mesh marks, concentric circles, saltire crosses, and other symbols scratched or drawn into parts of the woodwork, especially around fireplaces, windows, and doorways, to catch and prevent the further invasion of evil into the home and family. Witch bottles (as they have come to be identified in the twentieth century) were another significant witch-fighting tool available to the Massachusetts Bay colonists. Like the marks on the walls and doors, they were designed to trap witches who in spirit form tried to gain entrance into their homes to make family members sick and die. They feared and hated witches so much that they were willing to use these “white magic” measures to defend themselves against the witch’s black magic. People hated witches, and it was said that Widow Ann Burt was one, so her life was in serious danger. In 1669 Phillip Reade accused the widow Ann Burt of Lynn of being a witch. The elderly woman had been practicing the healing arts while her husband was alive, but for eight years after his death at aged seventy, continuing to sell her medicines and healing services became essential to sustain herself in her widowhood. Reade may have been protecting his value as a healer by trying to eliminate the competition, but several others also bore wild-eyed, frightful testimony against her that sounded quite damning. The evidence painted her to be the opposite of Puritan morality – a devil-worshipping witch. Claims were made that the old widow had tormented her patients, tried to get them in league with the devil, appeared and disappeared at will and even exercised control over a cat and a dog to do her bidding. The ill patronized her nonetheless, though some came to rue their decision, complaining that Burt took demonic satisfaction in the fact that her remedies only caused their pains to increase. Bethiah Carter, aged 23, deposed that when her sister Sarah Townsend was still “a maid,” she had been “sorely afflicted with sad fits” and that on an occasion when the two sisters were both ill, their father had carried Bethiah to Boston for treatment, but only took Sarah “too Lin too an owld wich” – the widow Ann Burt. Bethiah also claimed her sister Sarah saw the widow Burt appear at the foot of her bed frequently, both day and night and also that Burt had said if she would believe in her God (insinuating that Burt meant the Devil), she would be able to cure her body and soul.[24] Madeline Pearson, Sarah and Bethiah’s mother, deposed that she had heard Sarah explain how, after Widow Burt had gotten her to bed, she had urged her to smoke her pipe, “and giving of her the pipe she smoket it and Sarah fell into the fits again and said Goodwife Burt brought the devil to her to torment her.”[25] Reade testified he was sent for three times to examine the ill sisters and found that Sarah was “in a more sadder Condiccion … but did playnly perceive there was no Naturall caus for such unaturall fits.” Finding Sarah rational on his fourth visit, Reade asked her the cause of her fits, “she tould me ... Burt had aflickted her.” When the girl had her worst fit an hour later, Reade asked her who afflicted her, “She Replide with a great scrich she had tould me alreddy and that she did Now Suffer for it.”[26] John Knight testified that he had seen Burt coming out of a swamp in her smock sleeves, a black handkerchief and a black cap on her head and then she suddenly disappeared; when he came into the house he found her there, wearing the same clothing he had seen her in at the swamp. When he asked her if she had been in the swamp, she denied it, saying she had been in the house the whole time to which he replied that she must be a “light headed woman” (crazy); he was standing by what he had claimed to have seen with his own eyes.[27] Jacob Knight told of an occasion when he was lodging under the same roof as the Widow Burt. While lighting his pipe in the same room as Burt, Knight told her he had come down with a pain in his head, then went back to his room, which was separated from hers by five doors. He stooped down to unloosen his shoe, then upon looking upward, “there was widow Burt with a glasse bottle in her hand.” She told him it contained something that “would doe my head good, or cure my head, ... [but] when I had drunke of it, I was worse in my head”. He then thought about how she had suddenly appeared in his room, separated as it was from hers by the five doors and a squeaky floor, “but I heard nothing & her sudden being with mee put mee into affright ….” The next day on his way to Salem, he saw a cat which then disappeared, followed by a dog that did the same (the intimation being that these animals were witch’s familiars spying on Knight for her as she had instructed them), then someone who looked like widow Burt goeing before mee downe a hill as I was goeing up it ....” The following night, in the clear moon light, he looked out his chamber window and “saw widow Burt upon a graye horse” in the yard “or one in her shape,” but when he awoke his brother, neither could see her. After his brother was again asleep, “shee appeared to mee in the chamber, & then I tooke upp a peece of a barrill head and threw it at her & as I thinke hit her on the brest & then could see her noe more at that tyme.”[28] Thomas Farrar similarly testified that his daughters were “in former time sorely afflicted and in ther greatest extremety they would cry out & roare & say that they did see goody Burtt & say ther she is doe you not see her kill her there she is & that they said several times and I have a son now in extreme misery much as the former hath bin and the doctor says he [the son] is bewiched to his understanding.”[29] Farrar’s description of his daughters’ hysterical reactions to their spectral visions of Burt were eerie portends of the Salem witch trials yet to come. Amazingly, despite the emotional testimonies, fearsome accusations, and spectral evidence presented against Widow Ann Burt by Reade and the others, there is no indication that she was convicted, which it seems, in retrospect, could only have been avoided by using a little hocus-pocus.[30] THE PIRATE For a time, Johann Casper Richter von Cronenshilt, lived a pirate’s life, although as one sanctioned by the government. He could have stayed in Lynn, living the sedate life of a country doctor, but the call of the sea was strong – and it was dangerous. The difference between a pirate and a privateer was just two sides of the same cutlass: sailing the high seas and attacking ships for their booty was done the same way with the same risks, but piracy meant not sharing with the crown. Some of Cronenshilt’s crewmates flipped over to piracy after he served with them. During his swashbuckling adventure, he was the doctor and surgeon for two English privateers at the same time. Court records of 1695 reveal the seafaring voyages of “Johann Casper Richter Van Cronadshilt of Lynne, Chyrurgeon" who took care of all the sicknesses and wounds among the crews of the privateers Dolphin and Dragon – “betwixt both Sloopes wee had but one doctor,” wrote one of the captains of the two ships joined in a single mission.[31] The Dolphin and Dragon were both sloops, sometimes referred to as “Man of War” sloops, being rigged out with cannons and letters of marque with which they were sanctioned by the British government to fight, capture or destroy, and plunder French ships. Voluminous court records first locate the two ships off the coast of the island of St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, working in “consortship” to attack and plunder a French ship, a pursuit that ended unsuccessfully. “Johann Cronon: Schilt[,] a Jerman,” was the one doctor for both ships, but sickness (especially contagious illness) and battle wounds could produce a sudden influx of patients in desperate need of the one doctor-surgeon, for which he would receive 100 pieces of eight plus his full share of plunder.[32] The alliance of the two sloops made their attacks even more withering for the victimized enemy; the tandem acted like a team of wolves at sea, circling around their prey then suddenly attacking together.[33] The two sloops finally had a victory on 2 March 1694, taking a French brigantine off Crab Island, then carrying the prize ship to St. Thomas; the plunder was valued at £400.[34] It was a win, but not the booty of their dreams. At the village of Samana, Hispaniola, the two captains wrote up a new mutual alliance with the strategy of finding and plundering “their Majesties Enemies” thousands of nautical miles to the north in the “River of Quebec” – the Saint Lawrence River.[35] By mid-May, the Dragon and Dolphin were being loaded with supplies and new crews in the important port of Salem, Massachusetts. Some of the two dozen men on each sloop may have felt proud to be fighting enemies of the crown, but if so, there were better opportunities for victories in the much bigger, world-class, British naval vessels, rather than the smaller, lighter-gunned but fast vessels in which they were risking their lives. The only certain reason that each member of the Dolphin and Dragon crews sailed the ocean, hunting for quarry, was for money – booty – treasure chests full of it. But the preponderance of depositions were aimed at the Dragon captain who had been taken to court by several former crew members, among them the doctor, Cronenshilt, for reneging on alleged promises to award them full shares of the booty. It was an even more significant share when their biggest prize turned out to be valued at over £14,000 ($2.8 million USD in 2020); a full share worked out to be £200.[36] Cronenshilt sued for £300 ($60,000 USD in 2020), including damages.[37] In the weeks leading up to their first sea battle with the French, the Dragon captain sent for Cronenshilt to spend time on his ship because they needed him more; most of the Dragon crew was unwell.[38] The Dragon added some men while traveling through the “Gutt of Cancer” (the Strait of Canso that separated Cape Breton from Nova Scotia), because some of their crew had become incapacitated.[39] (It was important to both crews that unnecessary extra men weren’t added to the evenly distributed crews of about two dozen on each of their sloops because more men meant smaller shares for each.) Though formally signed on to the Dolphin, the doctor faithfully administered to the crew of the Dragon from that point through the rest of the voyage and in so doing, he found himself amid the blood and gore of naval battle. The Dragon and their aggressive captain would twice engage French vessels without the aid of their consort, the Dolphin; injuries and deaths occurred during both engagements and Cronenshilt was in the middle of it all. The first victory was against the French ship, St. Joseph, on 25 June 1694.[40] The Dragon captain ordered all of his able-bodied crew on deck to join the fight, so Cronenshilt probably did his share of fighting as well – he owned a cutlass and a short carbine rifle and bayonet, favorite weapons of ship crews for use in the close, confining shipboard combat on narrow decks among the tangle of rigging.[41] When the British privateer defeated the French fly boat, the Dragon captain instructed surgeon Cronenshilt to go aboard the vanquished prize to look after his men that had boarded and fought on it, being that many of them that were “out of order” (wounded), “which he did.”[42] The valuable French boat could be taken to a British port back in New England where it would be sold with its handsome cargo of wines and brandy.[43] The Dragon took a second French ship a month later on July 27th.[44] In that action, four of the Dragon’s crew were killed and two were wounded in the fight – a quarter of the original crew had become casualties in the one engagement, and Cronenshilt applied his surgical and healing skills to everyone who still had a pulse.[45] The two ships finally being reunited after the second battle, the Dolphin captain’s quarters became a makeshift hospital and the captain lamented over the loss of his inner sanctum, “my Doctr hath and does take care of his wounded men – which I have taken on board my Vessell and in my Own Cabbin – and Suffered all manner of Stinck & naughtyness therewith.”[46] The Dolphin captain and various crew members attested to Cronenshilt’s skill in “Physick & Surgery,” confirming his claim of the “Care[,] paines & Medisines wch. the pet[itioner] did take & expend” upon the captain and crew of the Dragon during the whole time of the voyage.[47] The court records don’t reveal whether he was awarded the £300, but he made it back alive and decided to henceforth keep his feet on dry land. With memories of rocking ships and dangerous adventures lingering freshly in his memory, the 33-year-old doctor married 22-year-old Elizabeth Allen in December of 1694, and they settled down in the serene, sylvan setting of her family’s property at Lynn’s Mineral Spring.[48] Family legend states that Elizabeth had been healed by him of some illness and at the end of the year they were married.[49] Cronenshilt was offered an opportunity to sign on as ship’s doctor with another boat heading out of Salem for the St. Lawrence in 1695, but he declined the high seas and another privateering adventure, having found safe harbor in marriage and babies.[50] In June 1700, “John Casper Rickter van Cronenshelt of Boston, Phisitian,” purchased his mother-in-law’s twenty-acre parcel of land in Lynn between Muddy Pond and Spring Pond.[51] The doctor and his wife lived by Lynn’s idyllic Mineral Spring Pond for a few years, then moved to bustling downtown Boston where they raised their family of five children. Cronenshilt purchased a home and property in 1705 near Scarlet’s Wharf in Boston’s North End.[52] He may have left privateering behind, but the salty air of piracy still lingered nearby. In 1704 John Quelch and six of his scurvy crew had been marched in chains from the gaol by forty armed guards, past throngs of gawkers, on their way to Scarlet’s Wharf and the waiting ferry boat. It took them to the gallows that had been set up on a nearby sand bar, where large crowds watched as the pirates were hung. Thomas Larimore, a former Dolphin crewmate and friend of the doctor (he had testified in defense of the doctor’s claim for a share of the plunder), also turned pirate and got tangled up with some of Quelch’s crew and the law in 1706. Cronenshilt might have hidden from view while watching such public spectacles of convicted pirates to avoid the possibility of some of the pirates calling out to their old friend and doctor, exposing his connection to the life that had now smeared into piracy. After the doctor’s death in 1711, an inventory of what had become his meager estate showed that while the doctor left behind his swashbuckling days, swashbuckling couldn’t be taken out of the doctor; despite having very little left, he had kept his cutlass, carbine, and bayonet to the end of his life – not at all helpful to a doctor, but very helpful to a pirate. * * * * * * As rugged as the struggle was for people to stay healthy in 17th century Massachusetts Bay Colony, it may have been ever harder for the healers to stay alive. They not only had to stay clear of sickness and death, but also the prejudices of those who suspected they were healing under the influence of piracy, witchcraft, or rum. ENDNOTES [1]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 46: Warrant, 31 March 1670. [2]. Suffolk County Supreme Judicial Court Files, manuscript (Massachusetts State Archives, Dorchester, Mass.), Folio 2025:Deposition of Phillip Reade, 5 November 1679. [3]. Middlesex County Court Records, manuscript (Middlesex County Court House, Cambridge, Mass.), Folio 116: Attachment, 23 September 1669. [4]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 116: Attachment, 23 September 1669 (emphasis added). [5]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 56: Deposition of Thomas Wheeler and Jonathan Prescott, no date. [6]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 56: Deposition of David Fiske, 13 April 1670; Deposition of Thomas Wheeler, 13 April 1670. [7]. Supreme Judicial Court Files, manuscript (Massachusetts Archives at Columbia Point, Boston, Mass.), No.1052: Deposition of Susanna Gleison, 5 September 1671. [8]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 48: Warrant, 27 August 1669; Deposition of Richard Rice, no date; Deposition of John Baker, no date; Deposition of John Buss, 1669; Deposition of John Farwell, 29 August 1669; Bondsmen’s petition, 5 October 1669. [9]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 53: Deposition of John Hayward, 21 June 1670. [10]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 67: Attachment to Ambrose Makefasset, 20 May 1674. [11]. Files of the Suffolk County Supreme Judicial Court, manuscript (Massachusetts State Archives, Dorchester, Mass.), No.2025: Deposition of John Dammond, 16 December 1679. [12]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 88: Declaration of Phillip Reade, no date. [13]. Files of the Suffolk County Supreme Judicial Court, No.2025: Deposition of John Dammond, 16 December 1679. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 88: Deposition of Sarah Hawks and Joseph Trumble, 16 December 1679. [14]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 88: Declaration of John Gifford, 5 November 1679. Sections in brackets fall beyond a torn edge of the page. [15]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 88: Declaration of Phillip Reade, no date. Sections in brackets fall beyond a torn edge of the page. [16]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 88: Declaration of Phillip Reade, no date. [17]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 88: Declaration of Phillip Reade, no date. [18]. Files of the Suffolk County Supreme Judicial Court, No.1052: Deposition of Cyprian Stevens, 13 April 1670. [19]. Files of the Suffolk County Supreme Judicial Court, No.1052: Deposition of John Heyward Sr., 13 April 1670. [20]. Files of the Suffolk County Supreme Judicial Court, No.1052: Deposition of John Buss, 13 April 1670. [21]. Middlesex County Court Records, Folio 53: Deposition of Francis Dudley, Ephraim Roper, and Thomas Wheeler, no date. [22]. Files of the Suffolk County Supreme Judicial Court, No.1052: Deposition of Ann Adams, 15 April 1670. [23]. Cotton Mather, Magnalia Christi Americana, Book 2, p.60 (emphasis in original). In his comments here, Mather also laid blame upon the growing popular adherence to fortune-telling, singling out by example, the 1684 publication, Delights for the Ingenious, by which “the Minds of many had been so poisoned, that they studied this Finer Witchcraft, until, ‘tis well, if some of them were not betray’d into what is Grosser, and more Sensible and Capital.” Getting people to stop their use of symbolic objects and actions to fend off witchcraft was a confusing message to preach to a people who had for centuries witnessed churches demonstrating the same willful use of faith-based symbolism, including the transubstantiation of blessed wine and bread into the blood and body of Christ and such clerical blessings as those given to farmers’ ploughs to fishing boats. See Matthew Champion, Medieval Graffiti: The Lost Voices of England’s Churches, (London, England: Ebury Press, 2015), p.26. [24]. Dow, Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, (1669), Vol.4, p.207. [25]. Dow, Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, (1669), Vol.4, p.209. It is interesting to note that all of what Sarah Pearson was alleged to have said about her experience with Widow Burt came from the depositions of her mother and sister; there is no record of Sarah giving her own deposition. Perhaps her “condiccion” and “unaturall fits” had temporarily emotionally disabled her from presenting coherent testimony or she might have been otherwise prevented from giving her testimony because it would have contradicted her mother and sister, and been more favorable to the woman who had treated her? [26]. Dow, Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, (1669), Vol.4, p.207. [27]. Dow, Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, (1669), Vol.4, pp.207-208. [28]. Dow, Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, (1669), Vol.4, p.207. A common element of witch lore was that they had “familiars” cats, dogs, and other animals that did their bidding, like spying for them. [29]. Dow, Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, (1669), Vol.4, p.209. [30]. An inventory of her estate was taken on 18 March 1672-3, which suggests that she survived the 1669 witchcraft charges and died about three years later. See Dow, Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, (1673), Vol.5, p.204. Note that she signed her will with her mark, which strongly suggests she was illiterate, unlike her husband, who was at least able to autograph his will. [31]. Sherriff’s Warrant (Boston, 18 MAR 1695; Lynne – emphasis added) and Deposition of Erasmus Harrison (Boston: 19 MAR 1695; betwixt); both in Suffolk County (MA) court files, 1629-1797, Case 3101, (on familysearch.org); see also Deposition of Abraham Samuel (Boston: 04 APR 1695), Case 3101. [32]. Deposition of Erasmus Harrison (Boston, 19 MAR 1695), Case 3101. See also Deposition of Christopher Weeks & Richard Nulande (Boston: 04 APR 1695), Case 3101 (Jerman); Articles of Agreement between Captain and Crew – Erasmus Harrison, Captain of the Brigantine Mary, Suffolk County Court (MA) court files, 1629-1797 (Boston: 01 MAR 1694), Case 3123 (on familysearch.org), (plunder). [33]. See Articles of Agreement between Captains Glover & Harrison (Salem: 20 MAY 1694), Case 3123 and Testimony of Erasmus Harrison, Captain of the Sloop Dolphin (Boston: 14 SEP 1694), Case 3123. [34]. Deposition of Erasmus Harrison (Boston: 14 SEP 1694), Case 3123. [35]. Deposition of Erasmus Harrison (Boston: 14 SEP 1694), Case 3123. [36]. Statement of Prize Value, Suffolk County (MA) court files, 1629-1797 (Boston: 02 APR 1695), Case 3123. [37]. Sheriff’s Warrant (Boston: 18 MAR 1695), Case 3101. [38]. Deposition of Abraham Samuel (Boston: 04 APR 1695), Case 3101. [39]. Narrative of Robert Glover (Boston: 10 NOV 1694), Case 3123. [40]. Narrative of Robert Glover (Boston: 10 NOV 1694), Case 3123 [41]. Deposition of Edmund Quash, Suffolk County (MA) court files, 1629-1797 (Boston: 01 MAY 1695), Case 3123. [42]. Deposition of Thomas Larrimore (Salem: 20 MAR 1695), Case 3101 (out); Deposition of Erasmus Harrison (Boston: 19 March 1695), Case 3101 (which). [43]. Admiralty Court: Condemnation of fly boat called St. Joseph, Suffolk County (MA) court files, 1629-1797 (Boston: 1694), Case 3123. [44]. Narrative of Robert Glover (Boston: 10 NOV 1694), Case 3123. [45]. Narrative of Robert Glover (Boston: 10 NOV 1694), Case 3123. [46]. Deposition of Erasmus Harrison (14 SEP 1694), Case 3123. [47]. Sheriff’s Warrant (Boston: 18 MAR 1695), Case 3101. [48]. Vital Records of Lynn, Vol.2, p.110. [49]. Harriet Ruth Waters Cooke, The Driver Family, p.268. [50]. Joseph B. Felt, Annals of Salem (Salem, MA: W. & S. B. Ives, 1849), Vol.2, p.245. [51]. Indenture (Lynn: 20 JUN 1700), Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986, Vol.18, pp.206-207 (online at familysearch.org; emphasis added). [52]. Land Sale (Boston: 15 OCT 1705), Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986, Vol.24, pp.122-123. In this record, Cronenshilt was called a surgeon. Lynn Massachusetts history - History of medicine - 19th-Century Health Remedies - Vintage Medical Ephemera - 19th-century medicine

Inventory of an Abandoned Life

by Andrew V. Rapoza © 2024

HAUNTED. The absence of life often lingers more persistently than life itself. In February 1870, a walk through the Marysville house was vividly unnerving, just like the ghost ship Mary Celeste would be three years later – they should have been full of life, but both the house and the ship were abandoned, eerie in their emptiness. The two-story Pollard home on 7th street in Marysville, California, wasn’t the most opulent residence in the community, but it was a fine home to be sure. Marysville sat at the edge of the goldfields and its population quickly swelled into a city when California’s gold rush was underway from 1848-1855. By 1870 the excitement had died down, but the little city was well established and still had wealthy people and nice homes. The Pollard’s home had eight rooms including three bedrooms, a bathroom, kitchen, dining room, and family sitting room, and a formal parlor to receive guests at the front of the house.[1] Yet a visit was anything but inviting; upon entering through the front door it seemed like the occupants had suddenly and noiselessly exited out the back. Every room testified of the family that lived there: furniture throughout, paintings on the walls, and curtains in the windows; a family bible, a photo album, and other personal effects were carefully placed and tastefully arranged. The family seemed to have given no thought to the possibility that that moment in their home would be their last and frozen in time. Winter had covered the neighborhood outside, but its lifeless silence was shared by the inside of the Pollard house. Gas lamps were positioned throughout the house, but each room remained dim without the glow of a single flame. A treasured piano, flute, and fife were ready to fill the home with music but not a note was heard. Two highchairs for tiny tots sat in the dining room but there were no children’s voices or laughter. A dog rug laid on the parlor floor, but man’s best friend was missing as surely as was the rest of the family. The first impression was made in the parlor; among its fine furnishings was an expensive forty-dollar carpet ($930 today), a walnut rocking chair and one of cane; a rosewood easy chair and ottoman, a mahogany card table, a sofa, and curtains framing the windows. Well-maintained, it was always ready to welcome visitors, but the cold silence of the room only hinted of times past when the Pollards entertained their guests. Walking down the hall and by the hat rack and table brought a large railroad map into view, showing the best routes for getting around the countryside – trips that would no longer happen. The dining room had a stove for warmth, a clock, the toddlers’ highchairs, and a top-of-the-line Grove & Baker Sewing Machine – at $90 the second-most valuable item in the house (over $2,000 today), ready to produce fine fashions for the family that would never get to wear them. A closet also waited, heavy-laden with its China dishes, soup tureen, gravy bowl, and spittoon, its silverware and silver-plated call bell and cake basket, its pitchers, pickle dishes, and crumb brush, glass goblets, cut-glass decanters, glass stand punchbowl, and engraved wine glasses – all at the ready for the meals that would never get eaten, the parties that would never be celebrated. The kitchen and pantry were well-stocked with everything needed to feed the family for a long time: 150 pounds of flour; 95 pounds of sugar; 50 pounds of salt; 20 pounds each of brown sugar and corn meal; 10 pounds of cracked wheat; a large box of raisins; 3 demijohns of vinegar, and 44 pint-size tin cans of fruit filled the storeroom. It was all ready to be cooked on the kitchen stove into fine meals and treats, but they sat unused on the shelves and floor; an eternal feast for field mice, perhaps – the only possible diners left in the empty belly of the uninhabited house. The cold lifelessness of the place was felt even more poignantly by going upstairs. The stairway itself was covered in carpeting held in place by stair rods – another non-essential extra that marked this the home of a successful family. The extra quiet it was to provide turned out to be entirely unnecessary; phantoms couldn’t have made less noise going up and down than the unused stairs in that vacant, silent home. At the top of the stairs was the children’s room which contained a small bureau and washstand on the carpeted floor and a child’s crib, covered with a mosquito netting bar – entirely unnecessary now that there was no blood left to suck. A bathroom between the bedrooms served the family’s needs with a looking glass, bath brushes, flesh brushes, nail brushes, and toothbrushes, a slop pail and injection pipe for enemas, a soap dish, bronze hooks, and a basin and sponge. None of it – the brushes, basin, or sponge – was any longer covered by the lathers of life; only by the dust of disuse in the dead-quiet, abandoned house. Mrs. Pollard’s bedroom was furnished with the finest of everything. The carpeted floor was adorned with a fine mahogany bedroom set; five feather pillows fluffed along the headboard of the bed. A matching mahogany bureau stood nearby, filled with Mrs. Pollard’s clothing, among which were thirteen dresses and seven skirts, plus stockings, garters, hats, unmentionables and more to complete every ensemble. Other personal items hinted at her efforts to stay in touch with family and friends far away: ivory rulers and an ivory paper folder, and a silver pencil case containing a gold pen. A bracket on the wall was decorated with cherished ornaments. Charles Pollard’s love for his wife was reflected in the pedestal of possessions he had put her on, but his bedroom furnishings were fairly spartan by comparison.[2] His bed and bureau were accompanied by a rocking chair, washstand, and two covered chamber pots. His bureau, however, was packed with the male equivalent of a clothing spree to make him presentable as an accomplished businessman. It contained sixteen shirts (eleven white), thirteen vests, eleven pairs of socks, eight coats and pairs of pants, five pairs of boots, three umbrellas, two pairs of red flannel drawers, two pairs of suspenders, handkerchiefs and cravats, a suit of gymnastic clothing, and the inevitable single, unmatched sock. Nested among the clothing was a double-barreled shotgun with shot and a powder pouch, and a five-shot Colt revolver. The shotgun was likely for hunting, but the revolver was almost certainly for protection – a precaution that was almost forgivable. Nearby was a trunk cryptically marked “EM-7”; it wasn’t just another trunk – it was the family’s treasure chest. It contained two gold rings engraved “Mrs. CPP” and “Mr. C. P. P.”, $12 in cash, a $950 life insurance policy, and $448.35 in gold and silver coins (valued at $10,428 today). These weren’t lucky finds of gold dust or nuggets from the gold rush; they were hard-earned, minted coins, stored away as an investment in the future. In total, their home, possessions, and money all proved the brief blush of success that the Pollard family had enjoyed; for Charles, it had been a long time coming. ADRIFT Charles Porter Pollard was born on 9 September 1834 in Hallowell, Maine, the second son and eighth child of George Pollard.[3] Two younger brothers followed Charles, but then death began its haunting pursuit: Samuel died in 1836 at just four months old, then Henry followed in 1840 at seventeen months.[4] In August 1846, when he was only eleven years old, Charles lost his mother.[5] His father, then 56 years old, had suddenly become a widower and the only parent of seven surviving children still under his roof. Three short years later, in January 1849, death had also come quickly for father George, too quickly for him to make a will, but he might have called in some favors by making arrangements for the care and safety of his children: by 1850 they had all been relocated to Salem, Massachusetts.[6] Three of Charles’ sisters were taken in by the families of a merchant tailor, lumber dealer, and tinsmith, and the rest of George’s children, including 14-year-old Charles, were put up with the family of Simeon Flint, a mason, probably in large part because he had married Ellen Rebecca Pollard, Charles’ second oldest sibling, a half-sister. [7] It may not have taken too much persuasion to get Charles out of the Flint’s suddenly crowded house – just six months after his father’s death, young Charles had sailed off to South America (Rio Grande de Sul, the southernmost point of Brazil, bordering Uruguay) on a voyage that lasted six and a half months. He was listed on the manifest of the Brig Russell of Salem as 14 years old and standing precisely at a diminutive 4 feet 8.5 inches.[8] The rest of the crew were between ages 20-25 and included a 1st mate, 2nd mate, and seamen, earning between $16-$30 monthly. Charles was listed as a “boy” with good reason: he came aboard just a kid in a man’s world. All hands were engaged in dangerous work daily; one fell overboard and drowned, and another left the ship when they got to Brazil. The previous captain of the Russell had been brought up on charges of flogging his cook with 68 lashes for refusing to continue on as cook.[9] Gaining his sea legs amid the rough, rowdy society of sailors, the short, young Charles earned $5 a month, making him a wage earner probably for the first time in his life. Within just a few months of his return to Salem, 15-year-old Charles signed on as a crewmember of the Bark Arthur Pickering.[10] He was on the Pickering when his former ship, the Russell, sailed into a hurricane, losing masts, sails, and the lifeboat on the brig’s stern.[11] But while the Russell was getting shredded in the South Atlantic, Charles was sailing safely in the Indian Ocean on the Pickering. It had already stopped at Zanzibar on the east side of Africa and Muscat in Oman on the Arabian Peninsula, and was skimming across the ocean at full sail to Bombay, India, when the hurricane was punishing the Russell. Death had haunted the lad during his few years of life, but it hadn’t caught up to him yet. After being at sea for over a year, the Pickering anchored back in Salem Harbor in June 1852. The sixteen-year-old seasoned sailor who walked down the gangplank had gone places and seen wonders that most boys only dared to dream about. Forty-three days later he was back to sea, again on the Pickering, bound once more for Zanzibar and beyond.[12] It was his third ocean voyage in three years. He had grown an inch and a half and his wage had risen by two dollars; now at age sixteen, he had traveled over 35,000 nautical miles. A little taller and a little richer; a little older and a little wiser. For reasons that in its wisdom, history has decided to leave a mystery, Charles then turned his back to the ocean and ventured deep inland, some 1,400 miles west of Salem, to the town of Hastings in the territory of Minnesota.[13] There in 1857 he had become a 22-year-old merchant – of something. But a month after he was doing business in Hastings, he left on another great adventure. He traveled down to New Orleans, took a ship going down to Panama by way of Havana, then boarded the train that traveled through the jungles to the Balboa, the end of the line on the Pacific coast. There he embarked on the steamship John L. Stephens bound for San Francisco.[14] His final destination: Marysville, California. Plotting his many travels on a map didn’t suggest a man on a mission but rather a life that was lost. ABANDONED The reason Charles Pollard was determined to go so far and through so much to get to Marysville, California, is as much of a mystery as what had driven him to Hastings in the Minnesota Territory. He had to know that the glitter of the gold rush had passed, and he could have chosen any of the many towns throughout the American West that were booming with potential, so this dot on the map seems more like just any port in the storm than the only safe harbor for this mariner-turned-pedestrian. And Marysville didn’t seem to be swooning with excitement over his arrival – the work he found there was just as a clerk in the Marysville Drug Store, hardly a glamorous opportunity worth travelling over 8,000 rugged and dangerous miles to obtain. But there he was, in late 1857, at 23 years old, boarding in his new employer’s house, unpacking a satchel filled with memories and worn-out boots, a half-pint bottle of hope, and a full gallon jug of solitude. Licking his wounds and putting his past behind him, Charles focused on his new job. Oddly, a medicine by his name had been launched in Marysville just a few years before his arrival, but Pollard & Mason’s Anti-Malaria Pills, as it was then known, was made by a Dr. Abiathar Pollard, a transplant from Vermont and if any relation to Charles, it was too far up in the family tree for him to have ever seen the branch. But just as well, because his new employer, Henry T. Kelly, was determined to continue competing with his own anti-malaria cure, Dr. Kelly’s Celebrated Fever & Ague Medicine; in fact, he never even carried the Pollard & Mason’s stuff in his store – and his store was stuffed with medicines. After three years in Marysville, Charles was ready to drop anchor for good: the 26-year-old bought the Marysville Drug Store, lock, stock, and barrel.[16] The drugstore started by Henry T. Kelly stood out well at 56 D Street, Marysville’s main thoroughfare. Kelly and then Pollard after him were both careful to mention in their ads the drugstore’s location next to the large local landmark hotel, the Western House. Banners reading “Marysville Drug Store” were attached across the two second floor walls of the business, plus mounted over the building’s façade was an oversized mortar and pestle that could help even the illiterate know the kind of business it was. Like the excellent location and notoriety of the building, Charles only changed the elements of the business that would benefit from being updated. Most notably, while his purchase included the right to manufacture Kelly’s private-label medicines under the Pollard name, Charles left the all-important and long-running malaria medicine under the name by which it had developed: Dr. Kelly’s Celebrated Fever & Ague Medicine. Charles’ nephew, 21-year-old George Benjamin Flint (Simeon and Ellen’s oldest son) came out to assist Charles in 1867 with his drugstore, taking care of some of the compounding of doctors’ prescriptions and making the proprietary items.[17] An inventory of the store revealed much about the business of selling medicine in Marysville and also about the customers. It catered to mothers and hunters, doctors and patients, children and animals; it was designed to be the destination for anyone who wanted to feel or look better. The show window had beautiful cologne bottles of ruby glass enhanced with gold gilt, some that were engraved, still others decorated with flowers, and extracts for dobbing on handkerchiefs; some bottles of pomade and hair oil may have been standing too long in the sun because the inventory noted they had become rancid. An interior showcase showed off many types of brushes, including rosewood crumb brushes, horsehair flesh brushes, infants hairbrushes, nail brushes, and toothbrushes, along with horn combs, a microscope, and field glasses, good for night and day. Fiddle strings and flypaper displayed next to galvanic bracelets and thumb lancets; sturgeon hooks hung nearby the carpenter’s pencils. Mothers could look through a large selection of nursing bottles and teething rings for their babies and nipple shields and pessaries for themselves. Doctors and those making home remedies had a wide array of medicinal ingredients from which to compound medicines, including quinine and digitalis, ipecac and ergot, licorice root and wild cherry bark, extracts of mandrake and wahoo, grains of paradise and dragon’s blood, snakeweed and cephalic snuff, and pounds of morphine, opium, and cannabis. Then there was an enormous amount of shelf space filled with the patent medicines of the day, which for the most part were packaged versions of opium, morphine, or cannabis. Star of the Union Bitters, Moffet’s Life Bitters, Pratt’s Democratic Bitters, and Hostetter’s Bitters vied for attention among heavily advertised brands like Perry Davis’ Pain Killer, Ayer’s Sarsaparilla, and Merchants Gargling Oil, and the boomtown’s demand for syphilis pills and specifics for gonorrhea. Many balsams and tonics could also be found at the Marysville Drug Store, like Cooper’s Magnetic Balsam and Schenck’s Seaweed Tonic, along with all sorts of liniments, pills, and plasters, sarsaparillas and worm syrups. The store’s most heavily stocked patent medicines were 348 boxes of Wright’s Indian Vegetable Pills for constipation, indigestion, and fever, and 288 boxes of Brandreth’s Pills for purifying the blood of a whole galaxy of diseases; the much higher quantities of these two products probably reflected their popularity rather than slow-moving stock.[18] Firmly entrenched in his own business, store, and adopted community, it was time for Charles to invite the love of his life to join him. Conjoined through his half-sister Ellen’s marriage to the Flint family, Charles had been anticipating the arrival of Elizabeth Maria Flint, the niece of Ellen’s husband, Simeon. Charles had almost certainly known and befriended Elizabeth a decade earlier, in the early 1850s, when he lodged in Simeon and Ellen’s house in Salem and Simeon’s niece, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Flint, was living just a few miles away in South Danvers. The two reunited in California with the arrival of Lizzie on the steamship Orizaba on 18 December 1862.[19] As if out of a page from a romance novel, they wed one week later, on Christmas Day in 1862. A year and a day later, on 26 December 1863, Lizzie gave birth to a son in Marysville; they named him Charles Flint Pollard. A few weeks more than two years passed before they had their daughter, Minnie Snow Pollard, on 12 January 1866. As the family grew, so did Charles’ proprietary line of medicines; his advertisements in Marysville’s newspapers heralded Pollard’s Extract of Coffee (a laxative), Pollard’s Rheumatism Pills, Pollard’s Sarsaparilla, Pollard’s Eureka Liniment, Pollard’s Tooth Powder, Pollard’s Jamaica Ginger, Pollard’s Flavoring Extract, Pollard’s Cathartic Liver Pills, and Pollard’s Compound Extract or Chemical Food, and, Charles promised, “These Medicines are put up under my immediate supervision.”[20] His Eureka Liniment must have been one of the best-selling medicines in his store; it was well-stocked with 354 small and large bottles of it. Charles was respected as “a prominent citizen” and “a prominent Mason, and he was elected to Marysville’s Common Council.[21] The Pollard family lived just five blocks from his store in the nice home on 7th Street, full of nice things. We might have been inclined to leave the Pollards at this point, since their story seemed destined to end “happily ever after” – but death was still stalking our tragic hero. BROKEN On 22 September 1868, Minnie Snow Pollard, the daughter of Charles and Lizzie, died; she was just 2 years 8 months old.[22] Her lifeless body laid at rest in their home on 7th Street for two days and then the funeral procession started at the home at three in the afternoon. The tragic loss of little Minnie started changing the family and the house they shared. Her crib was heavy with her loss and the front parlor where her body was laid out had become a temporary mortuary. When the funeral cortege followed her coffin to the Marysville Cemetery, her absence became total and complete. Her body was laid to rest in the remote cemetery, one and a half miles from where she had brought life and happiness to her family. The somberness of mourning hit them hard and things started to change. Pollard’s drugstore advertising had been brisk and frequent for several years until Minnie’s death; in fact, in the September 22nd issue of the Marysville Daily Appeal, a half-column ad ran for the Marysville Drug Store – the largest Charles had ever run – appeared incongruously close, just three columns away, from Minnie’s obituary. After this issue, his advertisements ceased altogether; everything just seemed to stop. His nephew and drugstore clerk, George B. Flint, left very soon after Minnie’s death, moving to Oakland to work at a drugstore there. A newspaper mention of his departure reported that he was filling “the same position with satisfaction to himself and employer,” intimating that the new situation was a stark improvement over his previous employment at the Marysville Drug Store where friction had apparently been building with Charles.[23] Charles Pollard’s life was already beginning to unravel. In late December 1869, right around their seventh wedding anniversary, Charles’ wife Lizzie was diagnosed with erysipelas, which was commonly called “St. Anthony’s Fire” because of the a red, raised, and painful rash on the skin; sometimes accompanied by blisters, fever, chills, and swollen nymph nodes and left untreated, it can spread to the heart valves, joints, and bones. Physicians of the time had no clue about its bacterial origin or how to cure it. Even diagnosing her sickness as erysipelas may have been incorrect, but there was one aspect upon which her physicians agreed: her case was hopeless.[24] The newspaper told the rest of the tragic and shocking story by telling the results of the coroner’s inquest: "During the wife’s sickness the husband has been broken of his rest; and since being informed that the illness would result fatally, Mr. Pollard has suffered the greatest mental agony. His drug store has been closed, and his whole time devoted to the duties required under the afflicting circumstances." "On Sunday night, while two kind neighbors were watching the dying wife, the frantic husband lay down upon his bed and soon after fell into a sleep, from which he awoke about 6 o’clock. During this sleep Mrs. Pollard expired." "The two lady watchers went below, where there was a fire. During their withdrawal it is supposed that Mr. Pollard got up, stole quietly into the adjoining room, discovered his dead wife, and immediately withdrew, threw himself upon his bed, drew a five-shooter and blew out his brains." "The discharge of the pistol alarmed the lady watchers, who apprehending what had occurred, went to the nearest neighbors and gave the alarm. Coroner Hamilton was notified, and on entering the room found Mr. Pollard lying on the bed, with the deadly weapon grasped in his right hand. The pistol had been discharged while held near the right temple, and death must have been instantaneous. The verdict of the jury was that the deceased committed the act of self-destruction while laboring under a fit of mental aberration." "[It was] an affair which created a profound sensation at Marysville in the closing days of the year 1869 … This community was shocked …"[25] Newspapers from around the region inevitably republished the gruesome news out of Marysville, adding some details not found in the report above. A paper from Sonora, California, 150 miles away, reported that Lizzie had died about two in the morning, four hours before Charles had woken up, which meant that when he found his wife deceased, rigor mortis was already well under way. They also suggested he was having some financial struggles that may have contributed to his self-destruction.[26] Apparently there was no suicide note left behind; Charles just lost it. He had searched his entire life for the unconditional love that had been stripped away in his youth, then found it seven years earlier with his bride, Lizzie, and twice more with the added blessings of his children. But then his little girl died, followed all too soon by the love of his life. It was more than he could bear; death had continued to haunt him and then finally shrouded him in the terrible darkness of utter hopelessness, loneliness, and despair. There was yet one more tragedy on that night of death and suicide that he would only realize when he was on the other side of the mortal veil: after a life mostly filled with the kind of loneliness understood only by orphans, his suicide had made his son, Charles Flint Pollard, age six, an orphan. The courts took matters into their own hands, as courts will do when a person dies intestate. They ordered complete inventories of the Pollard home and drugstore and it was, indeed, complete, accounting for every item, from the cache of gold and silver coins to the bottles of rancid hair oil; in all, the inventory ran 183 pages. It was impossible to read the house inventory without seeing through the eyes of the inventory clerks as they stood in each room, observing and noting everything. The rooms of the house were undisturbed, other than the bodies having been removed, and there was no mention of the bloody bed coverings under Charles’ corpse; those would have had no value to the estate so were probably removed and destroyed. The Colt five-shot revolver had also been removed from his fingers and placed back in his bureau next to the shotgun, but it could still be used again, so was assigned an inventory value of five dollars. The only evidence of physical hardship in Lizzie’s room was a cane-bottomed “invalids chair” needed during her sickness. Like the inventory of the lifeless house, the abandoned store’s inventory had filled each item with purpose and told the store’s story, almost as if someone was narrating it aloud. It too, had frozen in silence, all business traffic having long-since ceased and the show windows, showroom, and back rooms increasingly looking like the proprietor had gone on vacation and never returned. The drugstore had become as still and lifeless as the house and was, in fact, closed forever. Although the massive store inventory provides great insights into the business and customers it supplied, those lively images it invokes are being viewed by staring at lists of inanimate objects that were gathering dust. No one was coming back to run the store; it had been abandoned by its stewards – an orphan of business. For his services, the coroner had been paid $53 in gold coins from the EM-7 hoard. The rest of the coins were used to pay the debts that Charles Pollard and the estate owed. The doctors, nurses, and others providing Mrs. Pollard care during her final sickness were paid from the estate as well, along with another man who was watching the property to keep it safe from burglars and other scoundrels who would take advantage of the well-publicized tragedy.[27] They assigned a guardian for young Charles Flint Pollard and saw to his needs, short-term and long-term. He was immediately given a horse figurine of gold and two gold shirt studs, valued at a combined $10, plus the silverware valued at $30. Since the orphan was entirely dependent on the estate for his support, he was given the homestead, its furnishings, goods, and trinkets, and the life insurance policy, all of which was assessed at a total value of $5,572 ($129,603 in 2023 USD). The final assessment of the store was that it needed to be put up for sale. The building itself was rented by Charles so was a non-issue for the estate settlement, but one bidder paid $5,000 in gold for the contents of the store in its entirety, which had an assessed value of $8,069.33. Depreciation on the drugstore’s stock and the large amount set apart as an allowance for Charles Flint Pollard, the minor child, had rendered the estate insolvent; the cash received for the store on 56 D street was insufficient to pay more than 56.5 cents on the dollar to the list of claimants who demanded payment for their bills that Charles had died without resolving. The newly orphaned Charles Flint Pollard was sent back East and lived the rest of his life in Lynn, Massachusetts, with relatives from his mother’s side of the family. He would marry and father three children, have several grandchildren, and die at a very full 88 years, hopefully finding more joy and peace along the way than did his father, namesake, and fellow orphan.[28] He would also become a bicycle dealer and later run a photography shop, perhaps having come to recognize that photographs help preserve a memory that would otherwise disappear in the lingering presence of absence. ENDNOTES [1] The inventory records for the estate of Charles P. Pollard are the basis of this story. The comprehensiveness of the inventories for his house and drugstore business provide extraordinary insights that have enabled this researcher to travel back to his life through the possessions and locations of his inventory. All references to the estate properties are from this one large source of data. See “Probate Court, Yuba County, Estate of C. P. Pollard, dec[ease]d; Inventory & Appraisement, Filed Janry 24th 1870, R. Eileman, Clerk” Ancestry.com, images 289-471. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8639/images/007603422_00290? [2] Charles Porter Pollard consistently used “C. P. Pollard” when he signed documents and advertised, but for the clarity and readability of this narrative, “Charles” and “Charles Pollard” have been used. [3] "Maine Births and Christenings, 1739-1900", FamilySearch https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F4HG-RRM Contributors to the FamilySearch biographical for George Pollard (KCMZ-4TV) show him married three times; however the conflicting suggests that there were actually two George Pollards living in Maine at about the same time; the first marriage to Judith Getchell has five children whose birthdates largely overlap those of the second and third marriages. I have therefore drawn the conclusion that only the second and third marriages belong to the father of Charles Porter Pollard, making him the husband of two wives and the father of ten children. [4] "Maine Vital Records, 1670-1921", FamilySearch https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:2HJP-G6M (1836 death record of Samuel Pollard) and “Find a Grave index,” database, Family Search (1840 death record of Henry Pollard) https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6Z7T-4QDM [5] "Maine, Faylene Hutton Cemetery Collection, ca. 1780-1990", FamilySearch (1846 death record of Hannah Pollard) https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QKM1-QMQK [6] "Maine, Faylene Hutton Cemetery Collection, ca. 1780-1990", FamilySearch (1849 death record of George Pollard) https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QKM1-QMQJ [7] 1850 United States Federal Census, Salem, MA, Dwelling 402; Family 634 (merchant tailor) https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8054/records/10086805? 1850 United States Federal Census, Salem, MA, Dwelling 298; Family 625 (lumber dealer) https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8054/records/10086771? 1850 United States Federal Census, Salem, MA, Dwelling 10; Family 18 (tinsmith) https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8054/records/10086771? 1850 United States Federal Census, Salem, MA, Dwelling 631; Family 1034 (mason) https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8054/records/10093319? [8] Salem and Beverly, MA, U.S., Crew Lists and Shipping Articles, 1797-1934 (Brig Russell, 23 JUN 1849 – 11 JAN 1850) https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/208728:61858? [9] Article, “Miscellaneous News Items,” New-York Tribune, 28 JUN 1849, p.1. [10] Salem and Beverly, MA, U.S., Crew Lists and Shipping Articles, 1797-1934 (Bark Arthur Pickering, 25 FEB 1850 – 16 MAR 1851) https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61858/records/141730? [11] Article, Passengers,” Boston Evening Transcript, 23 NOV 1850, p.3. [12] Salem and Beverly, MA, U.S., Crew Lists and Shipping Articles, 1797-1934 (Bark Arthur Pickering, 28 APR 1851 – 16 JUN 1852) https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61858/records/144747? [13] Hastings, Dakota, Minnesota Territorial Census, 21 SEP 1857, Dwelling 5, Family 5. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939Z-YG9N-CH? [14] Articles, Passengers,” The Sacramento Age, 4 NOV 1857 (departure from Panama); and “Arrival of the J. L. Stephens,” The Sacramento Bee, 4 NOV 1857 (arrival at San Francisco). [15] Early advertising promoted Pollard & Mason’s Anti-Malaria Pills but after the first few years, the name was permanently reversed to Mason & Pollard’s. For the story of Dr. Abiathar Pollard and Mason & Pollard’s Anti-Malaria Pills, see blog post of 14 OCT 2024 on promisingcures.com, “Prospectors, Fool’s Gold, & Nervous Laughter.” [16] The purchase was documented in advertisement, Daily National Democrat (Marysville, CA), 31 MAR 1861. [17] George was registered in Marysville in 1867, a druggist in Ward 2, the same ward where his uncle had been set up as a druggist since 1861; see “Supplemental List of the Great Register of Yuba County,” p.3, California Voter Registers, 1866-1898 Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2221/records/3524753? [18] All of the inventory records of the Marysville Drug Store are found in “Probate Court, Yuba County, Estate of C. P. Pollard, dec[ease]d; Inventory & Appraisement, Filed Janry 24th 1870, R. Eileman, Clerk” Ancestry.com, image 301-471.” https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8639/images/007603422_00290? The inventory was done months after the deaths of Charles and Lizzie Pollard, so the drugstore, like the house had been vacant for months, quiet and unchanging. [19] Find-A-Grave Memorial for Elizabeth Maria Flint states that she took the same travel route across the isthmus of Panama as did Charles, traveling on the steamship Orizaba and arriving in San Francisco on 18 DEC 1862, a week before her marriage to Charles; however, no source is cited for the information, so more research is needed to substantiate this. [20] Pollard-branded products are found in “Probate Court, Yuba County, Estate of C. P. Pollard, dec[ease]d; Inventory & Appraisement, Filed Janry 24th 1870, R. Eileman, Clerk,” images 323, 338-340, 354, 358, 360, 364, 367, 373, 381; see also Advertisement, The Marysville Appeal, 20 September 1868, p.2. [21] Articles, “Doings in Sixty-Nine,” Daily Appeal (Marysville, CA), 22 DEC 1904, p.7 (citizen, Council); and “Suicide of C. P. Pollard,” The Union Democrat (Sonora, CA), 1 JAN 1870, p.2 (Mason). [22] Death notice, Marysville Daily Appeal, 22 SEP 1868, p.2. [23] Article, “Personal,” The Marysville Appeal, 14 OCT 1868, p.1. [24] Article, “Doings in Sixty-Nine,” Daily Appeal (Marysville, CA) 22 DEC 1904, p.7. [25] Article, “A Tragic Affair,” Daily Appeal 28 DEC 1869, p.3.; also see Article, “Doings in Sixty-Nine,” Daily Appeal (Marysville, CA) 22 DEC 1904, p.7. [26] Article, “Suicide of C. P. Pollard,” The Union Democrat (Sonora, CA), 1 JAN 1870, p.2. [27] “Probate Court, Yuba County, Estate of C. P. Pollard, dec[ease]d” Ancestry.com, image 447 and 460. [28] The Lynn Directory, Massachusetts, 1920 (Lynn, MA: Sampson & Murdock Company, 1920), p..536 and business ad for “Pollard the Kodak Man,” p.1022 ; also see biographic details of Charles Flint Pollard on FamilySearch.org: https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/94GJ-WX5 Lynn Massachusetts history - History of medicine - 19th-Century Health Remedies - Vintage Medical Ephemera - 19th-century medicine

Gallery

Treasures, secrets, and fascinating finds that will appear in future blog posts! .

19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies 19th-Century Health Remedies

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(2).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)