- Andrew Rapoza

- Dec 18, 2025

- 19 min read

Updated: Jan 13

Discovery of Vermont's forgotten family of natural bonesetters.

AUTHOR'S NOTE:

I realize this blog was just posted yesterday, but as I continued to research the Chase family, I found that my previous research of Ebenezer Chase, father of Elmina, was incorrect. I had inadvertently tapped into another man by the same name who lived in Andover, not Athens, Vermont. Andover is about 14 miles northwest of Athens and there was an Ebenezer Chase in both locations during the same timeframe. I have therefore removed references to the Ebenezer Chase of Andover and replaced it with the story of the Ebenezer Chase of Athens who was, indeed, the husband of Betsey and father of Elmina and her siblings. Elmina's father is referenced throughout the blog post; consequently, changes have had to be made everywhere he is mentioned.

The result of these changes is that the history of bonesetting within the Chase family of Vermont has been improved with valuable details. The only way for me to make all my readers aware of these changes was by republishing the post and deleting the original version. I'm sorry for the confusion I may have cause for those who read the blog in the last 24 hours, but I steadfastly insist on providing factual histories on this website - anything else is just a piece of fiction and historically pointless. Thank you for your understanding, forgiveness, and continued support.

PREFACE

It sat there in the American Glass Gallery Auction Catalog #42 looking old, tired, and worn out. Next to the sleek, tall vial that shared the auction block for Lot 250, it wallowed fat and frumpy, neglected and forlorn. Light struggled to pass through the old glass that was still smeared inside with the greasy concoction it once held. It was certainly not at all like some of the auction’s other dazzling, richly colored bottles that ended up selling for more than I’ve ever spent for a car.

Nonetheless, the squatty little misfit was the one bottle that tugged at my heart. It had a fragrance of history – a very personal story waiting to be told. Repeatedly I bid up to as much as I could afford … then I bid once more, hoping it would not cost me as much as I had just committed. When the dust of bidding warfare settled, I was stunned to see I had lost the battle – Lot 250 went to the victor and that wasn’t me.

I felt devastated and empty inside: I had spent many days that plunged deep into the night, researching the Frost and Fire Ointment and its maker, Mrs. Dr. Ryder of North Randolph, Vermont, and my research had harvested several dozen pages of historical information about this fascinating woman. Full of information but no bottle to call my own, I was the adoptive parent who had gone all out, getting the baby’s room painted, decorated, and beautified for the precious arrival that the stork delivered to another at the last minute.

But this story needs to be told, so I’m sharing it with you here today. Through the kindness and gracious support of John Pastor, owner of American Glass Gallery, I have also been enabled to share images of the bottle that inspired this blog post to happen. Let’s get to it.

RELOCATION TO PERFORM RELOCATION

To truly understand Dr. Mrs. Ryder, it’s essential to go back to her roots. She was born on 14 April 1822, the ninth of twelve children in the Chase family of Athens, Vermont. Half way through the birth order, the girls were given names that sounded like an incantation: Almira Saphrina, Elvira, Elzina Eliza, and Elmina Eusebia, our protagonist; perhaps it was inevitable with parents named Ebenezer and Elizabeth. Although they gave their daughters names that were awkward and strange to our ears, they were typical of their time, but most everything else about the Chase family was offbeat.

Ebenezer Chase was a native of Maine and was also a healer. He learned the healing art from his father, also named Ebenezer Chase and also a doctor. Father Ebenezer was said to have had a large practice in Sebec, Maine, until he suffered a tragic end at 54 years old by drowning in Sebec Lake in late December 1828 (perhaps by falling through the ice?).

At least by the time he was 18 years old, Ebenezer (Elmina's father) had moved far from his central Maine home to establish his own career as a healer in Windham County in southeastern Vermont. There he settled, married, and raised his family. After the births of their first two sons at two other towns in the county, their next ten children were born in Athens, Vermont. The village center consisted of a church, a store, a post office, and a blacksmith shop with a tavern and a few mills nearby; the locals grandiosely nicknamed their small cluster of civilization, "The City." It was, in fact quite small, like most rural Vermont towns and villages of the era, reaching its zenith in 1820 at 507 residents, of which nine, almost two percent of the population, were in the Chase house.

Ebenezer was a bonesetter; he made a specialty of "[setting] broken limbs and long-standing dislocations; [he] had a high reputation for reducing fractures after other doctors had failed." (While there is no documentation proving his father was also a bonesetter, it is highly unlikely that the 18-year-old spontaneously began using bonesetting techniques when he began his own career almost 300 miles away from his medical mentor.) The scarcity of practitioners in the ancient bonesetting method, combined with his apparent bonesetting skill caused him to be called upon to travel from his new residence in Vermont to patients in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, and Canada. Most rural homes in northern New England had one or more occupants who made their family's traditional medicines from the plants they grew in the garden and picked in the woods and fields. While we today would be mystified by how an Athens woman of 1840 made remedies from Hollyhock blooms, black cherry bark, wormwood, butternut twigs, dandelion roots, and cranberries, it was bonesetting that was the mysterious cure to colonial and Victorian Americans; therefore, Ebenezer Chase of Athens, Vermont, was a healer in demand near and far.

Elmina Eusebia’s mother, who was best known as Betsey, was remembered in her 1846 obituary as “the famous Doctress,” although her fame was likely limited to notoriety among an apparently wide collection of patients and friends. The posthumous praise was carried by several newspapers published across half the state, in Brattleboro, Woodstock, and Rutland, most likely because she had been well known and respected over that large swath of Vermont and her passing was therefore expected to be mourned by many. There is no indication what type of healing methods she used; perhaps she learned some of her skills from her husband.

HEALING IN THEIR BONES

Cookie crumb trails of evidence point to the Chase household being open to any form of healing that didn’t involve medical school and bonesetting was considered an identifying characteristic of the Chase family. At least eight of the ten Chase children who lived to become adults provided healing services; we just don't know at this point whether just one, several, or all of the healing children practiced bonesetting, but one of the Chase scions identified himself in an 1876 advertisement as “one of the original family so well known in this state many years ago as the famous BONE SETTERS …”

The oldest of the Chase children, Ebenezer Jr., was called “the celebrated Indian root doctor”; his wife was also listed in Vermont’s earliest almanac as an Indian Physician (Walton’s, 1839), and their 17-year-old son Lorenzo told the public when his father died in 1846 that he and his mother would continue administering medicines to all those afflicted who would call on them. The pretentious teenager then revealed he had already been treating them for a few years:

I also hereby certify, that during the last one or two years and … during the protracted illness of my deceased father, that I have prescribed medicines for several hundred patients, … call and give me a try…

In the Chase family, practicing medicine without a formal medical education wasn’t inappropriate – it was standard practice; all of the healers in the family did it. Ebenezer Jr’s brother Isaac was a practitioner in both “the botanic school” and “the German system of medicine” (homeopathy) and his daughter became another “pioneer physician,” learning medicine in the bedroom and kitchen instead of the classroom and laboratory. Elmina’s older sister, Almira Saphrina, was also credited with the gift of doctoring people. She was remembered for taking the ill into her home where she would nurse them back to health with her homemade soups and stews. All of the medical practices of the Chase family were sympathetic to each other. Indian medicine and botanic medicine were virtually synonymous; homeopathy was based on infinitesimal amounts of plant-based material, and eclecticism blended the elements of nature into its arsenal. The large Chase family developed a reputation for being “eminent for their medical skill and knowledge and seemed to have inherited a strong tendency to the healing art.” To their credit, they were each remembered at the end of their lives as popular physicians, thus proving the axiom in an 1837 newspaper article that while bonesetters and others didn’t earn a degree, they earned a ‘degree’ of notoriety by their successes.

Healing was the sap that ran through the Chase family tree and it flowed freely into the branch that was Elmina Eusebia Chase. Under the sprawling trees of quiet Athens, Vermont, the Chase family home was a hive of busy bodies; Elmina was surrounded by all sorts of relatives and family healers with Mother Betsey as its queen bee and Father Ebenezer sometimes buzzing off to respond to urgent requests for his bonesetting skills. The medical method for which Elmina developed notoriety in the press was the very rare and specialized bonesetting skill that was passed on within families from generation to generation; Elmina almost certainly inherited her talents from the combination of both parents.

A QUICK HISTORY OF NEW ENGLAND BONESETTING

Over the more than two centuries that Europeans had crossed the ocean and become New Englanders, most of the thinly settled rural population relied on generational family self-sufficiency, learning to fill the gap created by the absence of shops and professionals. Home-taught and homemade were essential skills in the 17th to mid-19th century: making stew, pies, and pudding, cough syrup and tonics; canning and planting, quilting and darning, and many more skills were passed down from grandparents to parents to children and on into the future. Bonesetting was possibly the rarest of medical skills that was practiced and passed down in just a few special families.

Bonesetting was most often practiced by men, probably because of the strength that was often required to reset dislocated bones; but during the late 18th century, a British woman and daughter of a bonesetter proved that women could be bonesetters too. She traveled the countryside in miserable clothes and called herself “Crazy Sally,” inferring mental instability or outrageous behavior, but she proved to have enough strength to reset a man’s shoulder without any assistance.

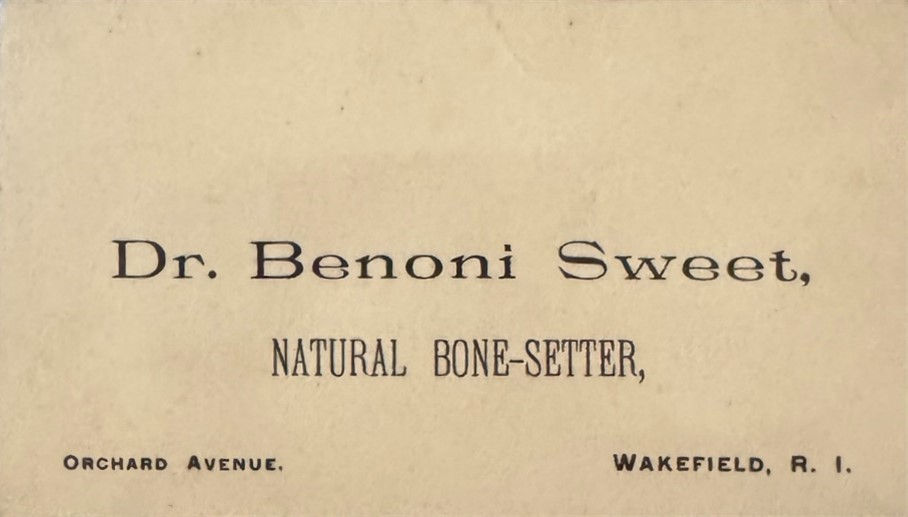

The Sweet family, based principally in Rhode Island, are the best-documented family of American bonesetters, a multi-generational dynasty. Some were especially in demand, like Job Sweet who, after the Revolutionary War, was summoned by Aaron Burr to sail from the old bonesetter’s home in Newport, Rhode Island, to Burr’s New York estate to reset the dislocated hip bone of his daughter:

In the evening [Sweet] … talked with her familiarly, dissipated her fears, [and] asked permission, in the presence of her father, just to let the old man [Sweet] put his hand upon her hip; she consenting, he in a few minutes set the bone; he then said, now walk about the room, which to her own and her father’s surprise, she was readily able to do.

Another distinguishing feature of the early American bonesetters besides their training from seasoned bonesetters within their own family was that they downplayed their skill; bonesetters from the Sweet family, for example, rarely advertised their services until the late Victorian era. Benoni Sweet (ca.1812) was a blacksmith. Waterman Sweet (ca.1830) placed an ad that mentioned he was a Bone Setter, but the central thrust of his ad was about “a lot of good Butter for sale” at his new shop in Providence. When bonesetter Stephen Sweet (ca.1843) was sought out by a newspaper correspondent for his special skills, he was found “industriously at work with his scythe in a field.” Neither he nor his equally sought-after bonesetter father published accounts of any of their remarkable cures nor even maintained a private list of the most difficult cases and when the writer was introduced to Stephen Sweet’s “troop of children,” he found that some were already beginning to prove themselves in the work of bonesetting.

THE PIONEERING MRS. DR . RYDER

Elmina Eusebia Chase emerged early from the home of her youth in Athens. She was a bride at 16 years old, having married a self-made healer named Ransellear Chillson, who was 21 years old; two and a half weeks later, she gave birth to their first child in Andover, about 19 miles from her childhood home.

In the next three years she had two more children. At about this time, when the 19-year-old mother was pregnant with her second, she began practicing as a physician. Why she began at this point in time is unknown; perhaps it was financial necessity compounded by an extended illness of her husband. He died in 1848, three years after she had borne him their third child. Consequently she was, at 26 years old, a widow and single mother of three children under 10 years old. She had also lost her beloved mother and mentor in 1846 and two of her brothers: Isaac, the homeopath, and Ebenezer Jr., the Indian root doctor. With her husband gone and a big chunk of the family that had been her world for sixteen years, Elmina had to survive on her own and protect her young cubs in the Vermont wilderness.

In the midst of the staggering losses of her husband, mother, and brothers, Elmina did more than just rebuild her life by putting herself out there as a physician. With inspiring fortitude and determination, she attended classes at the Woodstock Medical School sometime between 1846-1850, about six miles away from her Bridgewater lodgings. She joined other area residents who attended classes at the school in “the basic natural sciences” (chemistry, geology, botany, zoology, etc.) Women weren’t allowed to attain a medical degree there before 1850, plus she was raising her children alone and beginning to work as a physician, so her limited time at the school was to improve her knowledge generally and in some aspects of her new profession (perhaps in chemistry and botany), even though she wouldn’t be able to get a degree as a result of her efforts. Elmina remarried to James Ryder late in 1850 and they moved to Randolph, Vermont, another 33 miles and several covered bridges further north into Vermont’s woods.

When the newly married couple and blended family reestablished themselves in Randolph, husband James redirected his career path onto a similar trajectory as his bride; he put away the hoe and for a time worked in a drug store as its clerk and he “also became known as a manufacturer of medical preparations" (perhaps he assisted his wife by preparing her medicines, like the Frost and Fire Ointment). All was not family harmony and optimism during the several transitions they were making; less than a year later, James posted a notice in the newspaper that his stepson, Elmina’s oldest boy, a 15-year-old minor “who has been under my care, has left my charge without a cause”; so he put all on notice that he wasn’t going to pay any bills that his wayward stepson may incur. Like the bones Elmina reset, the relocations of home and family caused some pains before the healing could begin.

MOTHER, WIFE, BONESETTER, PHYSICIAN

In short order, Elmina’s three Chilson children left the familial nest over the next decade by skedaddling at fifteen, marrying at sixteen, and dying at thirteen; but the losses were replaced with another brood during her second marriage, in 1853, 1857, and 1862. No details of her medical career appeared during these years that she was delivering and nurturing her second family, but soon thereafter Elmina’s healing works blossomed in print. Her husband’s service in the Civil War (for which he was registered as a physician) also contributed to her increased attention to home and family. She had been practicing medicine for some twenty years, but it took a back seat to her role as mother.

When James returned from the war, Elmina emerged again in an active and accelerated role as a physician. In 1863 James had paid the license tax for being a physician, but in 1864 it was Elmina who was charged with the physician’s tax. She gave medical exams to veterans applying for pension increases due to wartime wounds and disabilities. In 1868 she reported that she had been doctoring one such veteran, George W. Badger, for years because he was

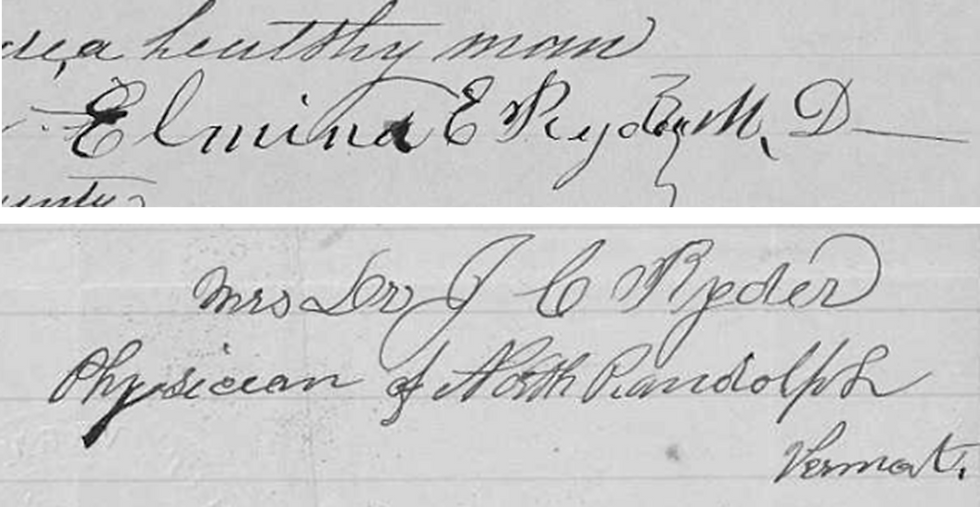

… laboring under a chronic disease of the Liver and Kidneys. Effecting the Spinal column and heart. producing palpitation and other diseases which wholy [sic] prevent his performing any labor … sufficient to sustain himself. … I have prescribed for the said [Geo. W.] Badger for the last 5 or 6 years and I don’t discover that he is e[n]joying no better health at this time than he was at the time that I first prescribed for him. I think that his disorders are such that he cannot be cured and made a healthy man

She signed her medical testimonies “Elmina E. Ryder M.D.” and “Mrs. Dr. J. C. Ryder / Physician of North Randolph.” The Justice of the Peace certifying the documents stated that she was “a physician respectable and reputable in her Practice.” Later that same year she filed her own claim due to her husband’s disability.

Badger, her sickly veteran patient, resided in Sharon, Vermont, some 19 miles from North Randolph, and she made many trips there to doctor him over the space of a half dozen years. She again appeared in the newspaper for providing medical aid to a schoolteacher in Woodstock, about 28 miles from her home, and when she tried to collect on her debts from the estate of a deceased patient in Hartland, 40 miles away. Her reputation was her advance agent and reminiscent of her mother; her whereabouts were being monitored for the public in the newspapers. As late as 1878, at the age of 56, she was located 34 miles from home, doctoring and apparently even doing some teaching, perhaps providing private lectures for women on health topics as was popular in that day: “Mrs. Dr. Ryder is out of town practicing most of the time this season. ‘Mina’ has been at White River Junction for some time, teaching, but is at home now.”

Perhaps her out-of-town medical travels gave her youngest son the opportunity for criminal mischief; at 16 years old, “Cash” (Cassius) Ryder was one of three rowdies who were arrested for disturbing the peace in the village of North Randolph one August night in 1878 when they “commenced depredations” on several others, “without any cause whatever.” On the other hand, when James, the oldest son from her second marriage, was 16 years old, he began assisting his mother in her professional labors. He went on to become an eclectic physician after attending the University of Pennsylvania in 1874 and doing some residency work at Bellevue Hospital in New York, in 1875; despite his formal training, he followed the example of his mother and made a specialty of the treatment of dislocations and fracture. Bonesetting had been passed down one more branch of the Chase family tree.

Bonesetting was a unique system of healing that required skillful, experienced hands and a strong knowledge of skeletal arrangement and required no medicine to perform the relocation of joints or resetting of bones; however, it was common for the bonesetters to have their own topical medicines to reduce inflammation and swelling, relax stiff muscles, quell pain, and return circulation to numbed limbs. In 1817-1818, Robert Hewes of Boston offered Hewes’ Nerve Ointment and in the early 1860s Stephen Sweet made his Dr. Sweet’s Infallible Liniment.

THE BONESETTER’S CURE FOR FROST AND FIRE

Mrs. Dr. Ryder also had her own topical product – Frost and Fire Ointment – that wonderful bottle that got away from me at the auction. The label of the small, twelve-sided bottle described the ointment inside as “unsarpassed [sic] for the cure of Burns, Scalds, Freezes and Chilblains, also old ulcerated sores.” “Frost” was the creative description of frostbite and chilled body parts it promised to cure and “Fire” referred to burns and scalds. The medicine’s name is creative genius, applying the opposite temperature extremes in one product name to constantly call to mind the totality of its healing benefits. The medicine had high viscosity, so the label instructed that the ointment needed to be warmed by the fire. Remnants of the thick ointment still coat the bottle’s neck, resolutely unmoved by the passage of time. The label on the auctioned bottle also has handwriting that crossed out the frequency of application in the printed instruction, “to be used once or twice a day,” replaced by “to be used at night.” More handwriting along the label’s top edge repeats the advice, “use at night.” The handwriting was definitely Mrs. Dr. Ryder’s (when compared to the letters she wrote as the examining physician for Badger’s disability petition). It was a personal touch, important enough to her to correct its use for the benefit of the patient; using it once instead of twice a day meant one bottle would last twice as long – clearly an instruction of a physician who was putting the patient before profit.

![Aqua medicine bottle with beveled corners; open pontil and short-style double-tapered lip, ca.1840-1845. [LEFT:] Embossing in the front sunken panel: Price's / Patent / Texas / Tonic; [RIGHT:] Embossing in the back sunken panel: Republic / OF / Texas. (Courtesy of PeachridgeGlass.com)](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/7441e9_879e2eb46a164ec281833b48bb93f2b2~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_1088,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/7441e9_879e2eb46a164ec281833b48bb93f2b2~mv2.png)