- Andrew Rapoza

- Nov 24, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2025

PAIN. Throbbing, stabbing, aching, distracting, excruciating, agonizing, unbearable PAIN.

Hannibal Lecter and S&M enthusiasts aside, most people don’t like pain. We’ll do just about anything we can to avoid it and when it does happen to us, we’ll do everything we can think of to get rid of it, as quickly as possible.

A toothache; a hangnail; a sprained ankle; a leg cramp; a migraine headache – every pain is one we want to have go away. You, me, and every one of our ancestors have tried almost everything to get rid of pain quickly. Sometimes what we try defies logic – and almost certainly flies in the face of science – but for thousands of years, in moments of excruciating pain, we have turned to methods and cures that win our praise if the pain goes away. That has often been the sole measure, whether it’s with two Advil pills today or a teaspoon of Wolcott’s Pain Paint over a century ago. When pain hits, our animal instinct just wants it to stop and the method, be it scientific or magical, really doesn’t matter. Be honest with yourself – you probably couldn’t explain the chemistry and active ingredients of Tylenol any better than your Victorian forebears could with Dr. William’s Pink Pills for Pale People.

The image above shows a Victorian era man plagued by a legion of demons in full attack mode, causing his headaches, sinus pain, toothaches, neuralgia, and more. To his right, the Grim Reaper emerges from his fog-shrouded netherworld, looking pleased at the pain being inflicted by his minions. In the same primal way that such imagery symbolically described their pain, Victorians also wrapped their aching heads around the idea that pain could be cured by magic.

Such a belief was likely passed down to them by old-timers in their lives who insisted that a special home-made medicine had to be swallowed during the waning of the moon or who still hung a horseshoe on their door. My own grandmother winced as she told me how her grandfather made his own medicinal tea from rat droppings because he distrusted doctors so much; he may have thought it was a magical brew but my grandmother thought he was full of crap.

America has a long history of reliance on magic and superstition to influence our behavior. Today’s post offers just a few examples for you to steep in your cauldron of possibilities for the next time your body screams at you, “I’M IN PAIN!”

Colonial Magic

As I shared with you in my post, “Weaponized Witch Bottles” (10 AUG 2024), colonists in North America relied on biblical passages that warned against the evils of witchcraft. They turned their empty wine and beer jugs into weapons to protect against the attacks of witches and their familiars, especially to protect the sick in their families. They further strengthened their defenses by hanging a horseshoe outside their door and making ritual protection marks around their doors, windows, and fireplaces – all the possible entry points for evil spirits to enter the home. Even biblically-inspired numerology was taken seriously: a braid of 12 garlic bulbs (symbolic of the 12 apostles) hanging behind the door was believed to prevent witches from entering the house; just 11 bulbs was nothing more than a bunch of smelly vegetables hanging on the door.

It was a time when magic was medicine and superstition dominated in the absence of science.

Victorian Magic

Two hundred years after the Salem witch trials, well after the colonies had merged into the United States of America, the country had survived its Civil War and two wars with England, and it leapfrogged into an era of electricity, telephones, x-rays, anesthesia, vaccines, blood transfusions, and the discovery that germs cause disease. Amid all this growth, modernization, and sophistication, it might seem like there was no longer a need for superstition and magic.

If that’s what you’d choose to believe, you have chosen … poorly.

Pain and disease had not been eliminated and science and medicine still had a long way to go. People were still having headaches and toothaches, rheumatism and sprains, and a bottle or box of medicine still offered low-cost, high-promise alternatives to doctors and dentists.

The absence of regulation in the medical marketplace meant medicine makers didn’t have to reveal the contents of their products and it’s fascinating how often they chose to claim their cure was MAGIC – far too many to list them all here, but a few examples were:

Bennet’s Magic Cure

Dr. Colwell’s Magic Egyptian Oil

Fink’s Magic Oil

Van’s Magic Oil – None other than a customer named Mrs. A. Pain wrote to the manufacturer, “We will never employ a doctor for cold or diphtheria while we can get your Magic Oil.”

Dr. Horbson's Magic Oil

Dalley’s Magical Pain Extractor

Dr. Hardy’s Magical Pain Destroyer

One look below at the Victorian poster for Renne’s Pain Killing Magic Oil vividly reminds us of how much we hate to hurt. His puffy eyes are almost squeezed shut; a large tear streams out of the corner; his lips look aquiver in misery. The head bandage under his jaw was usually a symbol of tooth pain, but this pathetic soul is also holding his stomach, apparently yet another locus of pain. We empathize with our young friend – we feel his pain.

Miserable in pain and apparent low on funds with a patched and tattered jacket, the young chap stands dumfounded in front of a drug store full of Renne’s Pain Killing Magic Oil; it’s frankly hard to tell if we are supposed to be witnessing that magical moment when he realized he had just found the cure for his woes or if his tear is because he couldn’t afford to buy the magical painkiller. Either way, he clearly wants some magic in his hard-luck life.

Notice that on the bottle, above the picture of Mr. Renne, was the magical medicine’s slogan, “IT WORKS LIKE A CHARM”; some newspaper ads for assured that its effect was “very magical.” It was, of course, a great word to hide behind, since the public were not invited to know the ingredients and proportions being used in the medicine. Medicines not promising magical results hid behind other fanciful names, such as Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root Kidney, Liver, & Bladder Cure, Pocahontas Barrel Bitters, and Smith’s Bile Beans. But “Magic” was more than a just camouflage; it was also a promise of potency and results even though sick customers had no idea why it would work for them. Subconsciously, people who enjoy magic shows want to be deceived. It fills us with wonder and awe and lets us believe that the world is full of unexplainable things. Magic gives us hope there are answers for problems and pains we could not solve ourselves.

Anyone who collects antique medicines knows that patent medicines had all sorts of names; those promising to stop pain weren’t limited to names implying magical ingredients. Perhaps the biggest selling pain cure of the century was the magic-free Perry Davis’ Pain Killer. Another example is from my own collection, Thurston’s XXX Death to Pain. Not only did its name promise to be the death of pain, but the triple “X” meant triple-strength – no indication of what, but it certainly sounded powerful!

Similar to the magic cures was a smaller subset of medicines called “mystic”. The name of Dr. I. A. Detchon’s Mystic Cure made it clear that the contents transcended human understanding and were somehow connected to ancient and perhaps occult mysteries. One of its ads explained that “Its action upon the system is remarkable and mysterious.” - take it, just don’t try to understand it.

Note that the bottle label explains that the Mystic Cure should only be used in combination with the Mystic Life Renewer.

Mrs. Wilson’s Mystic Pills from Toronto, Canada, was the perfect name for a medicine designed for the many diseases and disfunctions of the mysterious female reproductive system. The title implied secrecy, the dark closet in which many high-strung Victorians wanted to have the subject hidden. The trademark shows the female angel holding a box of the medicine in her right hand and her left hand pointing to the banner that displayed the “Mystic Pills” part of the name. An enlargement of the knuckles actually suggests the angel may be using the middle finger, but let’s just say it's the index finger!

For at least some of the many late-19th century remedies, the evocative words “Magic,” “Magical,” “Mystic,” or “Mystical,” in their name were used as more than just convenient marketing adjectives; they were designed to attract those customers who continued to harbor the centuries-old beliefs in magical potions, hoodoo, astrology, charms, and promises of good luck and fortune. The reason so many medicines seemed magical in their result was most likely due to the active ingredient (besides alcohol): opium, morphine, cocaine, or cannabis - they were each dangerous in excess but truly potent and successful in temporarily diminishing or eliminating pain.

Of course each era has also had its critics. Just like there were colonists who insisted there was no such thing as witchcraft, magic and mysticism had its detractors in the Victoria era. In 1900, Missouri’s Joplin News-Herald complained bitterly that “Americans are still believers in magic …” The newspaper pointed to a single factory of “magical devices” and found that it produced crystal balls and “not less than 5,000 divining rods and many other similar contrivances which are supposed to have the virtue of locating gold mines or hidden treasure.” – and the newspaper was disgusted that gullible fools would spend their money on things supposedly imbued with magic:

For one of these treasure indicators a farmer will pay from $15 to $35, and then, neglecting his toil, firm in the conviction that he has a truly magical device that will bring him untold wealth, he will tramp for days and even weeks over the old fields he had farmed since boyhood, seeking the gold mines and buried treasure the “magician” has assured him is there.

Medicines made in the name of “Magic” were another clear evidence of a portion of the population still hanging on to remedies emanating from the occult universe. In fact, even as the new Food and Drug Administration clamped down on specious patent medicines, magic oils and the like lingered, defiantly, deep into the 20th century.

Digital Magic

So now, dear readers, we sit in front of the screens of our cell phones and computers, reflecting a little smugly at the centuries of Americans who have believed in and resorted to magic, luck, and the mystical. But while our country may have continued its forward march in medicine, science, and technology, we are clearly far from giving up our superstitions and symbolic acts for warding off evil, eliminating physical and emotional pain, and encouraging good “mojo.”

Many doctors still administer placebos and patients often believe those harmless pills have made them feel better. Copper bracelets have never been proven to improve health, but many swear by them, nonetheless. (No offense intended to the placebo or copper bracelet manufacturers.) Family, friends, co-workers, and sometimes even strangers will say “bless you” after you sneeze, to ward off illness. And lots of Americans still act out in similarly irrational behavior today to improve, protect, and bring comfort to other areas of their lives in the midst of an often harsh and painful world:

Since 1952, fans of the NHL hockey team, the Detroit Red Wings, have thrown a dead octopus on the ice for “good luck” in the playoffs, despite the fact that the team has won only 7 Stanley Cups in the 73 years that octopi carcasses have slid across the Detroit ice. Oh, and catfish are similarly tossed onto the ice to invoke good luck for the Nashville team, and plastic rats keep getting flung into a hockey rink just north of Miami after a player killed a rat in the locker room with his hockey stick before the game and then scored two goals with that stick.

After you eat your Chinese food, do you throw away the fortune cookie or do you open it to see what the fortune says? (… And does the rare fortune that promises, “Great wealth is coming your way,” get quietly tucked into your pocket?)

Do you save the turkey wishbone to engage in a little post-Thanksgiving tugging match for luck?

Have you noticed that tall buildings usually have no 13th floor selection in the elevator? The architects and engineers didn’t forget how to count.

For the last 51 years, Lucky Charms cereal has featured marshmallow bits in the shape of such luck-laden symbols as blue moons, four-leaf clovers, and horseshoes. (My guess is that witches can’t eat that cereal.)

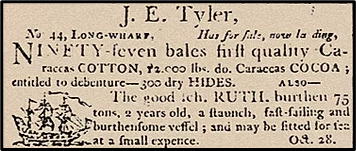

![Paul Revere, "A view of part of the town of Boston in New-England and Brittish [sic] ships of war landing their troops! 1768." In the left foreground is Long Wharf, starting in the city and jutting out into the harbor. The wharf extended into the harbor a half mile at one point, but this image shows landfill and Boston's buildings already surrounding some of the wharf. The wharf is surmounted by a long row of buildings that were the merchants' warehouses, counting houses, chandleries, etc. Map, Chicago, Ill: Alfred L. Sewell, [1870]. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/7441e9_a8b85ccd032341d5a40e4b6d7a0c2cbf~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_624,h_401,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/7441e9_a8b85ccd032341d5a40e4b6d7a0c2cbf~mv2.png)