Living the Dream

- Andrew Rapoza

- Aug 14, 2025

- 26 min read

Updated: Sep 1, 2025

224 years ago, while others were trying to figure out what it meant to be an American, one man was already defining the American Dream.

Today’s blog post isn’t about a promising cure but it is most definitely about a promising life.

I’ve been collecting advertising trade cards for a solid 40 years now. There are some beauties in my collection and some rare ones too, but it had seemed almost impossible to add an Early American trade card to my personal trove of ephemeral treasures; it's been an unfulfilled dream.

American trade cards were in use at least as far back as 1722, but examples from before the end of the Civil War are almost exclusively found in museums and a small handful of private collections. They’re rarer than hen’s teeth – and far more desirable. Absolutely dream-worthy.

However, in the last few months I’ve been able to add the Dr. John Curtis trade card (New York, ca.1865) and the British trade card (ca.1825) of John Conquest, hatmaker. (I’ve shared their stories with you this past May 6th [Curtis] and June 10th [Conquest]). Please check them out!

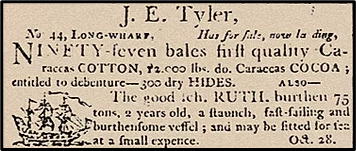

This trade card of John E. Tyler dates back to 1801. To fully understand its significance, you need to know the detailed backstory. Yes, there’s a lot to read, but it’s the only way to discover the whole story this very special trade card is trying to tell. The past is still trying to talk to us.

A FIRM FOUNDATION (1766-1790)

In 1766, achy, weary travelers seven miles north of Rhode Island stopped in the town of Mendon in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The stagecoach rest stop was 37 miles from Boston, according to the ancient milestone marker that is still standing in the town's Founder's Park, by the side of the original Middle Post Road. The rugged, undulating dirt road was jarring and tiring (George Washington complained about it) but nonetheless the vital artery connecting Mendon to Boston; it was the difference between going nowhere and going to the hub of their colony’s universe.

Riding another mile up the road towards Boston, travelers passed the south edge of the 600-plus acre Tyler property. The Tylers had been a prominent family in Mendon for generations since it had become a town a century earlier. John and Anna Tyler farmed their large property and had two children within a few years of their marriage: daughter Anna in 1764 and then son John in 1766.

Let me put this in perspective: 1766 was 259 years ago; slavery was still legal in Massachusetts and a decade before the 13 Colonies became the United States; the Boston Massacre wouldn’t happen for another four years and the Boston Tea Party three more years after that. Before dealing with wartime turmoil, however, the Tylers’ world was tossed upside-down when farmer John’s wife died in 1772; a few weeks later, the newly motherless John junior turned six years old. Despite the devastating personal loss and the challenge of suddenly becoming the single parent of two small children, John Tyler senior risked everything by participating on a committee of six Mendon men who drafted a formal protest to the various acts of Parliament that violated colonial rights and privileges, imposing duties or taxation on the Massachusetts Bay Colony. At a town meeting in March 1773, the committee of six drafted nineteen resolutions, starting with “… all Men have naturally an equal Right to Life, Liberty, and Property”; it was the first time such sentiments were put in writing in the American Colonies. The protest and refusal to accept the Crown’s impositions and seizures of liberties put every man who signed them at great personal risk, but they bravely voted nonetheless:

… that the foregoing Resolves be entered in the Town Book that our Children, in years to come, may know the sentiments of their Fathers in Regard to our Invaluable Rights and Liberties. [emphasis added]

John Tyler probably wondered whether putting his name to those words was sharing his patriotic values with his two motherless children or leaving them his farewell address.

In 1774 Britain closed the port of Boston, prompting Mendon citizens to write new resolves, urging the colony to “suspend all trade with the island of Great Britain until said act of blocking Boston Harbor be repealed and restoration of our charter rights be obtained.”

In response to the British attacks against the colonists in Lexington and Concord, on 19 April 1775, Mendon's soldiers mustered at Founders' Park and marched on to Boston by way of Middle Post Road; Private John Tyler was one of those soldiers, marching past his farm and probably his sobbing 11-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son as he headed to an uncertain future.

Private Tyler’s first tour of duty was nine days, stationed in Roxbury to prevent an advance of British troops by land into the colony from Boston. Eleven months later, Tyler had raised a company in Mendon and neighboring towns, was named its captain, and reported to Roxbury again, to join the ongoing siege of Boston. Captain Tyler and his company also spent the winter of 1777-1778 with General Washington at Valley Forge, but in March he was back in Mendon; the 47-year-old married a second time to a woman 21 years younger – she was just 11 and 13 years older, respectively, than her new stepdaughter, Anna, and stepson, John junior.

With the exception of some skirmishes in the South and the western frontier, the war was decisively concluded by the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781. At the cost of many valiant lives, the colonists’ liberties and property had been restored and their independence from Britain gained.The formal peace treaty was signed in 1783 by which time Captain Tyler’s little boy had become a young man and a student at Harvard University. At 20 years old he was one of 45 graduates in 1786, gaining his Bachelor of Arts degree.

Back home from the war, John senior was able to build the value of his estate to £1,990 – over a half-million dollars (in 2024 USD) and to enlarge his family through his second marriage. He fathered five more children between 1779 and 1788; then, just two months after his last child’s birth, the vigorous father and husband, wealthy farmer, and valiant veteran of war suddenly died. With his future seeming far more promising than when he had marched off to war 13 years earlier, he was killed in a moment of cruel irony by the falling of a large limb off a tree that he was in the process of cutting down.

From his father’s death through 1790, John the son was now being recognized by the courts as John Tyler, Gentleman of Mendon, a title typically reserved for those of high social standing, education, and wealth (usually inherited wealth). And he was single.

BUILDING BLOCKS (1791-1793)

The 57-year-old John senior didn’t anticipate his untimely accidental death, so he hadn’t prepared a will. In 1791 the court made his oldest son and namesake the administrator of his father’s estate, but even in his role as the first-born male, and the most educationally accomplished in his small family, he did nothing to pad his portion of the inheritance; he neither pushed to gain the entire estate or the double portion often accorded to the eldest son. His stepmother was given the widow’s third of the estate and the remainder was divided equally between him, his sister, and their five stepbrothers and stepsisters. The seven children of Captain John Tyler, ranging from 24 to 3 years old, each received exactly £119-3-8 (about $30,040 in 2024 USD) – equal to the penny. In another episode of brutal irony, John’s older sister Anna died while the court was in the process of distributing their father’s estate to the family; John was made the executor of her estate as well.

John’s education and ambition were steering him away from farming. A few months after his father’s estate was settled, “John Tyler, Gentleman” began showing up in records as “Dr. John Tyler,” a physician in Westborough, Massachusetts, 13 miles north of Mendon. He was listed as a physician there from August 1791 to November 1793. During that time he was awarded a courtesy (ad eundem) Master of Arts degree from Yale University in September 1792 and eight days later he received payment from Westborough for his attendance and medicines provided to one of its paupers.

Westborough was a small town – only 118 houses in 1791 – and there was already a popular physician named Hawes who had lived and practiced there for almost three decades, doctoring the town’s ill, making and dispensing his own medicines, and even pulling teeth. He had also become an influential leader there as its town meeting moderator, town clerk, and one of its selectmen. Money was obviously tight in the small town as Dr. Hawes often had to accept bartered goods in the absence of cash for his services – “everything from rum to pudding pans.” He also supplemented his income by hiring out horses and renting rooms in his home for lodging.

If John Tyler had real intentions to make the practice of medicine his career, Westborough seemed an unlikely location for an aspiring doctor to settle down. Clearly smart and well educated, it was incongruous for the new doctor to practice medicine in a very small town dominated for decades by a well-established physician (after all, there were only so many pudding pans a single guy needed!). Whatever his motivations were to go to Westborough, he left there with building blocks that would shape his future.

The few years John Tyler spent in Westborough were pivotal because of his association with the prominent Parkman family. Breck Parkman, a wealthy merchant, had a profound impact on the trajectory of John’s career. Three generations of the Parkman family had been tightly connected to Westborough’s Congregational Church where Breck’s father, the Reverend Ebenezer Parkman, served through much of the century as its first minister. There, on 10 November 1793, the church’s records reveal, “Doctor John Tyler[,] upon his public profession of Religion was baptized[,] it not having been done for him in his infancy.” The 27-year-old’s submersion in baptismal waters was most likely witnessed by his business mentor, Breck Parkman, and one of Breck’s children in particular – Hannah, who was just 13 when John had first arrived in town and 15 years old at the 27-year-old doctor’s baptism. In the years ahead, she would become his wife, her father would become his business partner, and John’s newfound religious faith would punctuate his path forward.

During his three years in Westborough, John Tyler’s life had undergone a personal revolution. He had arrived there as the lone surviving member of his birth family but he left Westborough with close ties to his new pseudo-family; he also gave up his career as a physician, became a merchant, was baptized a Christian, and went to Boston to start over. Like the new country around him, he was beginning life anew.

THE NEW NATION (1794-1800)

The fact that John Tyler could choose to live, work, and have property in Boston was the fulfillment of a nation’s dream; the 13 British colonies in North America had won the right to unite as an independent nation. The port of Boston was once again wide open to ship and receive goods with the world. The patriotic dreams of Captain Tyler had come true: his son was able to enjoy his unfettered rights to life, liberty, and property, becoming a merchant and building his life in Boston. The city that had been embattled and blockaded to choke it into subservience was now alive with ambition and freedom. Like the rest of the citizenry throughout the United States, Bostonians could proudly identify with the bald eagle, a uniquely North American species; it had been chosen in 1782 as the Great Seal of the United States, the new nation’s symbol of strength, freedom, and courage; Paul Revere had it adorn his own trade card.

John Tyler staked his claim to American success by moving to Boston in early 1794; within a few months of the doctor being baptized in Westborough he had resurfaced as a merchant in Boston. In 1796 he was listed as a retailer on Cambridge Street in the heart of the city, down the street from Samuel Chamberlin’s “Medical Cordial Store … at the sign of the Blue Bottle.” Tyler’s shop was near the wharves, the heartbeat of the city. The entire east side of Boston bristled with shipping docks like the back of an agitated porcupine.

The most dramatic protrusion into Boston Harbor was Long Wharf, jutting a half mile into the bay’s deep water, allowing the biggest ships to dock there and unload their large cargoes. It was as long historically as it was spatially. Looking through a spyglass on a clear day in 1726 at the end of Long Wharf, the body of pirate William Fly might be seen hanging in a gibbet cage in the harbor. In 1761 the Boston Gazette advertised the sale of Negro slaves “just imported from Africa” at No.19 Long Wharf. During the Revolution, the British landed at and evacuated from Long Wharf. A long line of warehouses, shipping offices, merchant shops, sailmakers, and ship chandlers were built upon the long wooden tongue of deck and pilings that stuck out far into the harbor. Businesses at No.19 and No.44 were nearer the west end that was attached to the land.

![Paul Revere, "A view of part of the town of Boston in New-England and Brittish [sic] ships of war landing their troops! 1768." In the left foreground is Long Wharf, starting in the city and jutting out into the harbor. The wharf extended into the harbor a half mile at one point, but this image shows landfill and Boston's buildings already surrounding some of the wharf. The wharf is surmounted by a long row of buildings that were the merchants' warehouses, counting houses, chandleries, etc. Map, Chicago, Ill: Alfred L. Sewell, [1870]. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/7441e9_a8b85ccd032341d5a40e4b6d7a0c2cbf~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_624,h_401,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/7441e9_a8b85ccd032341d5a40e4b6d7a0c2cbf~mv2.png)

Newspaper advertisements were used to announce the sale of goods unloaded by recently arrived ships. Addresses were listed for the shops and warehouses on and near the wharves where the particular goods could be purchased, usually along with the names of the business owners. In 1798, however, the building at No.44 Long Wharf was ownerless and identified simply by the number; whichever ship captains had docked on the other side of the wharf from the empty building mentioned their location at Long Wharf by simply stating it was “opposite No.44.” In 1799 the location remained vacant and just a reference point from which to find other things:

FOR SALE. / The schooner POWDER-POINT, 82 tons, one year old; now lying opposite No.44, South side Long Wharf. …(23 MAY 1799)

For CHARLESTON, (s.c.) / The brig CYRUS … will sail in a few days … For FREIGHT or PASSAGE, (having good accommodations) apply to the Master on board opposite No.44, Long-Wharf … (25 JUL 1799)

In January 1798 the editor of Boston’s Columbian Centinel newspaper noted that the empty building had what amounted to early Federalist-era graffiti scrawled across the front:

KINGS ARE NUISANCES

Although the snarky message could have been the expression of a dated opinion about England’s King George III, it’s more likely to have been referring to the sitting president John Adams, who was viewed by some of the population as despotic, or even George Washington, the concern being that the creation of the office of president just allowed another monarch to rule.

Vandalism had not been limited to the docks; other business locations in the city were being hit in 1799 and the business owners were getting fed up:

One Hundred Dollars Reward

is offered for the discovery of the infamous Villains, who on Saturday Night last defaced the Sign-Boards and Shops through Cornhill, Market Square and Union street. Whoever will bring to light the perpetrators of that work of Darkness so that they may be convicted thereof, shalt receive the above reward, on application to SAMUEL WHITWELL. N.B. The sum of near Six Hundred Dollars is subscribed, for the purpose of bringing the offenders to condign punishment. ... [emphasis added]

Perhaps the anti-royalty scrawling at No.44 Long Wharf was evidence the empty building had some elements of undesirability that kept it vacant for so long and encouraged visual vandalism; if so, the price may have been adjusted to make it attractive for the right enterprising business to make a try at the location. By at least 16 October 1800, John Tyler had set himself up at No.44 Long Wharf; there he offered for sale 25 large barrels of “Cogniac & Bourdeaux Brandy … 5 yrs old of the best flavour” and 50 barrels of “elegant white sugar.” He may have been there as early as February 1800, when someone at No.44 offered “A Few boxes of old Havannah Segars, manufactured from genuine Cuba Tobacco …” and again in April 1800 when 44 Long Wharf advertised, “WANTED, A BRIG FROM 130 to 160 tons, to take a freight to Holland.”

The fact that the busy city of 25,000 had other men also being identified in the newspapers as John Tyler may have been the reason that Boston’s new 35-year-old merchant sought out a legal change of name in March 1801:

John Tyler, of Boston, in the county of Suffolk, son of John Tyler, late of Mendon, in the county of Worcester, deceased, shall be allowed to take the name of John Eugene Tyler. [emphasis added]

As soon as the court approved his request, he immediately began using his new middle name and initial to single himself out to his customers. It was a simple but important change: John Tyler (no middle name) was selling goods at No.44 Long Wharf from 1800 to March 1801, but starting in April 1801, newspaper advertisements were identifying the proprietor as John E. Tyler, J. E. Tyler, and John Eugene Tyler – every possible version other than just his two birthnames. Bursting at the seams with enthusiastic determination to succeed in the new nation, the man with a new name, new business address, and new career was ready to shout it to the world.

THE NEW AMERICAN (1801-1803)

The same exultant spirit of eagerness and patriotic nationalism floated through Boston at the dawn of the new century, especially among the docks of the merchant trade. They vividly remembered the economic suffocation of the blockade during the war and were determined to reverse the pains of the past into a future full of promise. The city-wide exuberance was reflected in Boston’s 1801 Independence Day festivities. The jubilant and patriotic celebration was marked by church bells ringing throughout the city, the red, white, and blue Stars and Stripes waving everywhere, and salutes being fired from the frigates Constitution and Boston in the harbor and Fort Independence on Castle Island. An orator exhorted a large gathering of his fellow citizens “to feel, and to be AMERICANS,” and many toasts were offered to the new nation; the American eagle finding its way into several:

May every savage beast and bird of prey that shall dare to infest this happy country, or to attempt any depredations either by sea or land, be caught and held fast in the talons of the American Eagle.

May it bring the Barbarians to a sense of their duty … and make them crouch to the American Eagle.

Boston's shop and tavern signs often echoed their owners' newfound postwar patriotism. In addition to the Golden Eagle Tavern (1784) on Brattle Street and the"Sign of the Eagle" (1798) on Fore Street where the Frigate Constitution tried to recruit its crew, there was the "Sign of the Yankey Hero" (1783) in Wing's Lane, the "Sign of the Boston Frigate" (1800) on Fish Street, and the "Sign of the Golden Ball" (1799) on Wing's Lane. While the latter doesn't speak clearly to our modern sensibilities as a sign of patriotism, the owner of the liquor business it marked explained his customers were invited:

... to the Golden Ball - where he hopes the gratification they will receive, will be as great, as was that of the gallant tars of America, when they were told what effect another AMERICAN BALL [i.e., the cannonball] which well deserves to be GOLDEN, had on a foreign insurgent [i.e., England]. [emphases as in original]

There can be little doubt that the advertising trade card John E. Tyler commissioned (the engraver is unidentified) reflected the same patriotic fervor from the son of patriot Captain John Tyler, Harvard graduate, and doctor-turned-merchant. The pride he felt in the promise of both the new country and his new business were illustrated symbolically by the bald eagle – bold, strong, majestic, independent, and free; its broad wings stretched out into spread-eagle position, ready to soar at any moment of its choosing, yet controlled enough to display the commission merchant’s business banner. The eagle’s head is haloed by glory rays, classic symbols of a divine origin, suggesting the sacred nature of its mission. When the J. E. Tyler trade card was created in 1801, it must have felt like Heaven was in his corner.

Palm fronds tied to the bottom of the eagle’s oval perch represented John Tyler’s new Christian resolve. The branches from the common desert tree were used to honor the Messiah's ultimate triumph over life's most severe obstacles – sin and death. The overall card design may also have intended to subliminally project the eagle in the role of a phoenix, resurrected as Jesus had been and as John Tyler was trying to become in his new occupation and city.

It's possible but unlikely that the image on John E. Tyler's trade card was a copy of a sign over his business. The various shops and warehouses on Long Wharf during the first decade of the 1800s were identified by a street number - like John E. Tyler's No.44 Long Wharf location - and none, including Tyler, identified their location additionally as "at the Sign of ...". When Tyler was starting his business on Long Wharf, building numbers were just beginning to replace expensive building signs as business locators and trade cards were increasingly becoming the preferred means to promote the business and impress the customers.

One thing that is quite clear from 18th and early 19th century advertising trade cards is that the designs were purposeful, symbolic, and well planned out to communicate a lot and make a strong, memorable impression about the business in a small space. There was nothing haphazard and accidental in the symbolism and design of the J. E. Tyler trade card; it was left to the viewer of 1801 and 2025 to intuitively figure out what those messages were. But the bald eagle was the new symbol of America and as such would have resonated strongly in Boston at the beginning of the 19th century. Having the trade card at home or tucked in a pocket made it an ideal memory aid to find Tyler’s business for the first time or to remember where it was when standing among the clatter and clamor of people, horses, carriages, oxen, and cargo-mounded wagons on the docks in busy Boston. The back of the card was blank, as most early cards were, so that the proprietor could record notes of pending or completed sales before handing it to the customer. This example has no writing on the reverse; it remains blank

The challenge for 21st century viewers is to overlook the inaccurate, almost cartoonish rendering of the bald eagle and the palm branches. The bird’s “bald” head is depicted as little more than an eye mask; the secondary feathers are entirely missing from most of both wings; and the head seems too large for a body that is far too short. Even the palm branches were likely created from the imagination rather than a Bostonian engraver's first-hand observation of Middle Eastern palms. The engraver was not trying to reproduce museum-worthy, ornithologically and botanically accurate illustrations.

What the card illustration lacked in scientific accuracy, it made up for in engraved elegance. Calligraphic flourishes and embellishments framed and highlighted the proprietor’s new name and the all-important address of his business, No.44 Long Wharf, Boston. The engraver’s linework was rendered in great detail, giving curving depth to the palm fronds, motion to the banner, scales on the feet, and finesse to the shafts and vanes of each feather. The high-quality paper stock was stiffer and smoother than the era's standard rag writing paper and, combined with the finely engraved linework printed on it by copperplate, the result intentionally conveyed the quality of the card, the new business, and the esteemed customer.

The card was almost certainly produced in a small print run, perhaps about 100 cards, and therefore strategically intended for the most preferred clients – the big-quantity and repeat-purchasing business customer. It was not a mass-produced piece of ephemera arbitrarily handed out to any man, woman, or child who happened to stroll by No.44 Long Wharf – that's what trade cards would become after the American Civil War, but John Tyler's world was long before the dramatic improvements in printing technology that allowed for much larger and cheaper print runs.

John Tyler’s own signature sometimes showed the same flair for calligraphic flourishes as those that were engraved on his trade card and he always demonstrated a refined skill and ease with a quill pen in his hand as it lightly scratched along the paper. There was no more hesitation in John E. Tyler’s command of his merchant business than he had shown in using a pen. With his name changed, his business established at No.44 Long Wharf, and his trade card printed, he aggressively engaged in the business of negotiating the receipt and sale of a seller’s goods to other businesses and sometimes the public. He did so on a commission basis, receiving a percentage fee for finding a buyer and selling the seller’s goods to the buyer. It was a business that relied on connections, establishing good business relationships, and conducting it in a good economic environment; any problem with the seller, buyer, or economy spelled trouble for the commission merchant. It was nothing like farming or doctoring, but he was boldly determined to make it work.

He promoted his clients’ ship cargoes ambitiously in several Boston newspapers throughout 1801, his first year in the commission merchant business at No.44 Long Wharf as John E. Tyler; his advertisements served as newsprint fanfare to announce that the world was coming to Boston in ships. He sold cotton and cheese, glassware and anchors, bushels of beans and boxes of spermaceti candles; German Steel and Swedish Iron; coffee from Port au Prince and Trinidad; a bunch of sugar from Hispaniola and St. Croix, and lots of rum from Jamaica and Tobago; superfine flour from Baltimore and Philadelphia; and coarse salt from Lisbon and Liverpool. While he sold to families, shopkeepers, and country traders, his focus was selling in large lots to businesses, even trying to advance-sell cargo loads he had contracted for that were still making their way across the ocean. He sold loads by large 18th century barrel measures: hogsheads, pipes, and quintals. Some of his largest lots included 4,400 gallons of Havanna molasses, 6,000 pounds of green coffee, 12,000 pounds of cocoa from Caraccas, almost 50,000 pounds (225 quintals) of codfish, 70,000 boards of lumber, and 10 tons of Swedish iron. He sometimes took the risk on time-sensitive merchandise like a load of fish, trying to find buyers for a quick sale before the deal stank.

To be successful, there were greater risks he would take than selling fish or glassware: he sometimes extended unsecured credit to his customers, letting them pay months later for a load of coffee, sugar, or rum today, and he sometimes advanced his consigners cash on the goods they consigned to him, on the expectation that he would be able to sell the load and recover his money and still make his profit. It was risky business. In March 1802 a fire spread late at night up Long Wharf, threatening all its businesses, including J. E. Tyler’s, as well as the wharf itself. It destroyed eight buildings, Nos. 2 through 8 Long Wharf, and headed up the wharf towards No.44. Buildings 9 and 10 were partially pulled down to arrest the progress of the flames. Tyler’s building was among those spared but he was also feeling the heat from other pressures.

Newspaper advertisements were a critical means to quickly broadcast what merchandise he was trying to flip. In 1801, his first full year of business, he ran sixteen ads (plus each ad usually ran for several issues); but his advertising frequency dropped in 1802 by more than half. In 1803 Tyler’s newspaper advertising dropped steeply again; he was running only a quarter of the ads he had placed in 1801. England and France were at war and although the U.S. tried to maintain its neutrality, both countries attacked American shipping, seizing the ships and their cargoes. To add to the uncertainty of the future, the Tylers gave birth to their first child in September 1803: Hannah Parkman Tyler. John’s business was struggling at the same time that his family was growing – he needed an ally.

WARTIME ALLIANCE (1804-1810)

In January 1804, the records of Westborough’s Congregational church noted, “Mr. John Eugene Tyler & Hannah Breck his wife were dismissed from us & recommended to the church in Boston, commonly styled the Old South.” The Tylers were determined to live in Boston but they needed help to make it all work. By April of that year, No.44 was vacant again and in May, Breck Parkman had a nephew who was running his own commission merchant business out of the same location, while John E. Tyler showed up at No.41 Long Wharf in August, perhaps a more affordable location than his former business a few doors down the wharf. In October, John’s father-in-law intervened, either to help John fix his business, or out of concern for his daughter Hannah and his grandbaby Hannah, or perhaps genuinely to help all three. The co-partnership took second-floor rooms at 83 State Street, a few blocks away from where Long Wharf attached to the city. The announcement stated that Breck Parkman, “the senior partner,” would continue to run his store in Westborough while Tyler and a third partner named Parker would work out of Boston, a few blocks from Long Wharf. In promotional literature for Chamberlin's Patent Bilious Cordial, the medicine’s newest agents weren’t listed as based in Boston but as “Parkman, Tyler & Parker, Westborough” – father-in-law Parkman was the company decision-maker and clearly in control, even from his home thirty miles away.

Both of the partnership’s two locations focused on “a great variety of English, India and West-India Goods, at inviting prices, by wholesale or retail.” The new partnership was broadening Tyler’s previous approach of selling large lots to substantial businesses; the new firm was now encouraging retail sales as well – selling “by the package or piece for cash or short approved credit” – especially to attract fashion-conscious female patronage.

The Napoleonic Wars continued to disrupt American shipping and trade. Engaged in a war for the control of Europe, Britain and France continued to impose trade restrictions, ship seizures and blockades. Despite the challenges, the new partnership of Parkman, Tyler & Parker was able to deliver on its promise to supply shiploads of foreign merchandise. Their seven newspaper ads over the span of two years, 1805-1806, announced a wide variety of goods from London and Liverpool including ladies’ purses, pearl buttons, and pocketbooks; opera glasses and Britannia tea pots, “bombazets, calamancos, ruffellets, and shalloons,” blue, brown, and “bottle-green broadcloths,” and a host of fashions for every season. In July 1806, during his busy efforts to make the partnership succeed, John Tyler became a father for the second time with another daughter.

In March 1807 the partnership was dissolved and a new company was formed, substituting Parker with Breck’s oldest surviving son, Charles. The new firm was called Parkman, Tyler & Parkman: Breck was 58, John was 41, and Charles was the junior partner at 22, apparently being taught the merchant business by his father similar to how he had been mentoring his son-in-law John. Throughout the balance of the year, however, hard times for ship owners and merchants continued. In late December President Jefferson signed the Embargo Act into law, prohibiting American ships from undertaking voyages to foreign ports; the act proved devastating for the American economy, particularly for port cities like Boston, where ships lay idle at the docks.

from Barbara Rusch, Thornhill, Ontario, Canada:

... your most recent blog ... is absolutely amazing. Once again you've woven these forgotten lives into the larger backdrop of the times in which they lived. It's so impressive the way you've captured their personalities, triumphs and failures. Love the symbolism inherent in the card itself, with its hidden religious implications. ... I congratulate you for this great piece. Probably your best yet.

I loved reading this! It was definitely intriguing and I'm SO GLAD I don't live back then!!!

What a fun read!

Excellent article, Andy. You are obviously a proud owner of that little piece of paper, and you brought it to life with your sketch of the owner. A very nice job of tying together the few known facts about his life in a fair and introspective way. Your article should be forever tied to that little piece of paper.